HIV/AIDS & U.S. Agricultural Workers

Updated February 2023

Click Here to download the fact sheet as a PDF file.

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a deadly virus that is a major health threat to the United States population and has also become a global health issue. If left undiagnosed or untreated, HIV can remain asymptomatic and eventually lead to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), a dangerous disease that severely weakens the immune system and leads to death. Lack of health care access due to legal, financial, geographical, and linguistic barriers coupled with a lack of material and social support all place an especially heavy burden on migratory and seasonal agricultural workers for contracting HIV and/ or AIDS.

HIV/AIDS Background Information

HIV/AIDS General Data

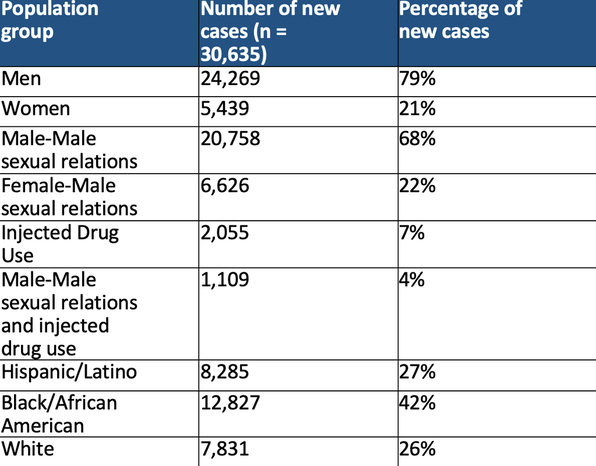

Table 1: Breakdown of new incidence of HIV infection within the United States in 2020

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a deadly virus that is a major health threat to the United States population and has also become a global health issue. If left undiagnosed or untreated, HIV can remain asymptomatic and eventually lead to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), a dangerous disease that severely weakens the immune system and leads to death. Lack of health care access due to legal, financial, geographical, and linguistic barriers coupled with a lack of material and social support all place an especially heavy burden on migratory and seasonal agricultural workers for contracting HIV and/ or AIDS.

HIV/AIDS Background Information

- The terms HIV and AIDS are often confused or used interchangeably, but in fact, they are very different. HIV can be transmitted through acts of unprotected vaginal or anal sex, blood transfusions or from mother to child through pregnancy, birth or breast milk. [1] Once infection has occurred, the virus destroys a specific type of blood cell, the CD4+ T cells, which are crucial for immunity and fighting diseases. [2] As the infection progresses and CD4 T cell counts decrease, it can then be diagnosed as AIDS.

- AIDS is determined by two main diagnostic methods: those of the Centers for Disease Control and the World Health Organization.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies an AIDS diagnosis based on the number or range of the CD4 cell count. This requires lab tests and blood work. Logically, the lower the cell count, the higher risk there is of an AIDS diagnosis. An AIDS diagnosis may also factor in symptomatic or AIDS-indicator conditions, such as Kaposi sarcoma, that often occur in patients with AIDS. [3]

- There are three stages of HIV infection: acute HIV infection, chronic HIV infection, and AIDS. Antiretroviral medications cannot cure an HIV infection, but they can help prevent an HIV infection from progressing to AIDS. [3,4]

HIV/AIDS General Data

- In 2020, 30,635 people received an HIV diagnosis in the United States. From 2016 to 2019, HIV diagnoses decreased 8% overall. [3]

- HIV and AIDS have a high chance of being prevented using PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis). Of the 1.2 million people who could benefit, 25% were prescribed PrEP in 2020. The efficacy of PrEP is 99.7%. Out of 2,670 participants tested, 99.7% stayed HIV negative through 96 weeks. [5]

- Certain populations are at a much greater risk for contracting HIV in the U.S. Persons residing in the South have an HIV prevalence twice that of those in the Midwest. Gay and bisexual men have the greatest burden of HIV infection (68% of new infections in 2020), and Black and Latino gay and bisexual men have the greatest risk. [3] Among women, heterosexual Black women experience the highest rates of HIV infection. [6] Of new infections in 2020, men reporting heterosexual contact counted for 7% and women reporting heterosexual contact accounted for 15%. [3] See Table 1 below for a breakdown of new HIV cases in 2020.

Table 1: Breakdown of new incidence of HIV infection within the United States in 2020

*Does not include prenatal cases

**Data could be lower than 2019 due to COVID-19 impact on HIV testing

**Data could be lower than 2019 due to COVID-19 impact on HIV testing

HIV/AIDS among Agricultural Workers

Prevalence

- Out of the 893,260 patients served by Migrant Health Centers in 2021, 1,017 were diagnosed with HIV. [7]

- Data regarding the incidence of HIV/AIDS in migratory or seasonal agricultural workers is limited. Some research has identified infection rates that range from less than 2% among Mexican agricultural workers to as high as 13% among Black agricultural workers. [8] However, no study to date on HIV prevalence among agricultural workers can provide a reliable estimate since past studies were non-random and often had a very small sample size. [9]

- Migration between Mexico and the United States has previously been highlighted in 2009 as a source of rising HIV/AIDS rates in Mexico, and Mexican officials now estimate that 30 percent of their country’s HIV/AIDS cases are caused by migrant workers returning from the United States. [10]

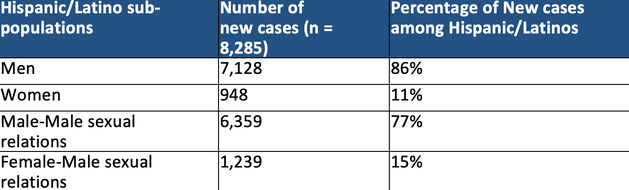

- Since prevalence data among agricultural workers is limited, the following data are about Hispanic and Latinos in the United States since the majority of agricultural workers identify as Hispanic/Latino. [11] Latinos in the U.S. disproportionately account for 27% of all new HIV cases even though they represent 19% of the population. [12,13] In 2020, the prevalence rate for Hispanic/Latino persons (625.8 per 100,00) was three times the rate for White persons (197.6 per 100,000). [14] The majority of new HIV cases in 2020 among Latinos occur among men, and specifically 77% among men having male-male sexual relations. [15] See Table 2 below.

Table 2: Breakdown of new incidence of HIV infection among Hispanic/Latino population in the United States in 2020 [16]

- In one study, it was noted that HIV diagnoses increased 7.8% annually between 2003 and 2006 along the U.S.- Mexico border. Increases were particularly significant for those men who have sex with other men. [10] A study of nearly 700 deported migrant laborers in Tijuana, Mexico found a relatively high prevalence of HIV among men (0.8%), but no cases were found among women. [17]

Knowledge, Perceptions, and Interventions

- CDC analysis suggests that Hispanic/Latino gay and bisexual men were less likely to be aware of their HIV status, less likely to use PrEP, and less likely to be virally suppressed (meaning they had symptoms of the virus and could spread the virus to their sexual partners), than other races and/or sexual orientations. [18]

- In 2019, 261 Latina seasonal workers in Miami-Dade County participated in a HIV prevention intervention, which incorporated social networking recruitment and education through videos, visuals and discussion about HIV prevention with condom use. Male condom use, female condom use, and HIV testing all increased as a result of this intervention. [19]

- In 2015, 178 farmworkers residing in migrant camps in North Carolina participated in a survey about knowledge of factors related to HIV transmission. Results showed that participants with knowledge that a condom protects against HIV were more interested in home test kits than those who did not know. Concern that HIV was a serious problem in their community was also associated with interest in using a home test kit. [20]

- HIV rates in South Florida, where many Latina seasonal workers live and work, are extremely high. [21] An intervention among Latina women in agricultural worker communities, including education about HIV risk factors, efficacy of HIV treatment, and prevention increased their knowledge significantly. Agricultural workers with a higher education level had higher HIV knowledge than those with a lower education level, and participants in a relationship had lower HIV knowledge than those who were single. [22]

- Many studies over the last few years have viewed the social context of migrant workers as a risk for HIV/AIDS as opposed to the individual acts of this group. For example, a study done in 2009 concluded that for Mexican men who migrate, loneliness is a feeling that plagues this population due to the social contexts that accompany the lifestyle: immigration status, traveling alone, physically arduous work, being away from family, etc. [23] Depression due to social-cultural displacement might increase high risk behaviors of HIV infection. [24]

- One study interviewed clinicians and health workers regarding the culturally significant implications of contraceptive use and safe sex practices among rural Hispanics of the Northwest. The majority concluded that openly discussing sex and sexuality is received with a lot of discomfort among this group, which may deter this population from actively seeking contraceptives or practicing safe-sex behavior. [25]

- Qualitative interviews with Mexican migrants diagnosed with HIV revealed that homosexuality and the resulting social and familial isolation often played a role in both HIV risk behaviors and mental and emotional issues post-diagnosis. Some of the participants’ stories also demonstrated a lack of awareness on how and where one could receive HIV testing. One participant learned of his HIV diagnosis after participating in an HIV screening at a local nightclub. [26]

Risk Factors and Behaviors

Unprotected Sexual Activity and Condom Use

- A study in 2010 found that knowledge of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STI) transmission and prevention was low among 100 male agricultural workers in North Carolina. However, among the 25 participants who reported having anal or vaginal sex within the last 3 months, 18 reported using a condom consistently and 40% mentioned being under the influence of alcohol during the sexual act. Because so few participants reported having anal or vaginal sex and inconsistent use of condoms, no statistically significant risk of HIV infection was found in the study. The authors assume this is due to the small sample size. [27]

- A behavior that may put some agricultural workers at risk for contracting HIV/AIDS is having unprotected sex with prostitutes. [28] A study of migrant male agricultural workers in northern California found that 39% of male agricultural workers reported that they had paid for sex, of which only 31% reported using condoms. [9]

- One study done on female sex workers who frequently work near agricultural areas reported that the greatest risks in their work involved assault or violence from clients and not being compensated, either in money or drugs, for their services. [28] The same study found that condom use is often inconsistent since workers have very few first-time clients. Most prefer a small number of regulars who they trust will not assault them and who will pay them, and whom they believe, there is a very small chance of contracting STIs.

- As for Mexican migrant women, a 2003 study found that of respondents who had two or more sexual partners, only 25 percent reported using a condom during sex. [29] Mexican migrant women, as well as migrant’s wives who remain in their country of origin, are vulnerable to contracting HIV due to risky behaviors of their male sex partners, which include unprotected sex with prostitutes, unprotected sex between men, and needle sharing. In a 2004 study, researchers found that 75 percent of migrant men rarely or never used condoms with their wives. [29]

Alcohol Consumption

- More time in the U.S. has been associated with an increased practice of HIV risk behaviors among laborers and agricultural workers in Florida. Agricultural workers who arrived more recently to the U.S. exhibited more HIV protective behaviors, including less frequent alcohol consumption and a greater willingness to use condoms. [30]

Infected needles

- Certain behaviors also put migrant workers at risk for contracting HIV/AIDS: including sex with prostitutes, inconsistent condom use, and alcohol and drug abuse. Intravenous drug use is uncommon among agricultural workers, but needle sharing may occur in some populations that inject vitamins or antibiotics. [6] A study of 300 agricultural workers found that amateur tattooing was more common than professional tattooing, which may place some agricultural workers at risk for an HIV infection. [31] However, this is likely minimal as only 6% of study participants had one or more tattoos.

Male-male sexual relations

- Sex between men is the highest HIV risk category in the United States for Latinos. It has been documented that men of color who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States are at an increased risk for HIV infection. Among Latinos, 77% of new HIV diagnoses in 2020 occurred among men who have sex with men. [15]

Access to Care

- Among the Hispanic/Latino population with diagnosed HIV, 74% received care, 59% were retained in care, and 65% were virally suppressed, remaining healthy without symptoms and not spreading the disease with sexual partners. [15]

- In 2020, 46% fewer HIV tests were administered among Hispanic/Latino people in non-healthcare settings than in 2019. [15] Characteristics of agricultural workers’ migratory lifestyle can contribute to an increased risk of contracting HIV and increase barriers to access HIV testing, treatment and prevention services. These factors include poverty, low income, low education level sub-standard housing, limited access to healthcare, limited English proficiency, mobile lifestyle and social isolation. [32]

- Considering these risk factors, some researchers have suggested incorporating HIV testing into routine care, urgent care, and the emergency departments in order to support this population of migratory agricultural workers and day laborers. [32]

References

1. What Are HIV and AIDS? HIV.gov. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/about-hiv-and-aids/what-are-hiv-and-aids

2. Vidya Vijayan KK, Karthigeyan KP, Tripathi SP, Hanna LE. Pathophysiology of CD4+ T-Cell Depletion in HIV-1 and HIV-2 Infections. Front Immunol. 2017;8:580. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00580

3. Basic Statistics | HIV Basics | HIV/AIDS | CDC. Published June 21, 2022. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html

4. The Stages of HIV Infection | NIH. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/stages-hiv-infection

5. DESCOVY FOR PrEP® (pre-exposure prophylaxis) Efficacy Results | HCP. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.descovyhcp.com/discover-clinical-trial

6. About HIV/AIDS | HIV Basics | HIV/AIDS | CDC. Published June 30, 2022. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html

7. UDS 2021 Data (unpublished).

8. Culturally Competent HIV Prevention With Mexican/Chicano Farmworkers - Julian Samora Research Institute - Michigan State University. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://jsri.msu.edu/publications/occasional-papers/132

9. Sanchez MA, Lemp GF, Magis-Rodríguez C, Bravo-García E, Carter S, Ruiz JD. The epidemiology of HIV among Mexican migrants and recent immigrants in California and Mexico. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37 Suppl 4:S204-214. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000141253.54217.24

10. Espinoza L, Hall HI, Hu X. Increases in HIV diagnoses at the U.S.-Mexico border, 2003-2006. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5 Suppl):19-33. doi:10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.19

11. Gold A, Fung W, Gabbard S, Carroll D. Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2019–2020.

12. HIV Incidence | Hispanic/Latino People | Race/Ethnicity | HIV by Group | HIV | CDC. Published September 19, 2022. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/hispanic-latino/incidence.html

13. Lopez MH, Krogstad JM, Passel JS. Who is Hispanic? Pew Research Center. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/15/who-is-hispanic/

14. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019. 26(1).

15. CDC FACT SHEET: HIV Among Latinos. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/racialethnic/hispanic-latino/cdc-hiv-group-hispanic-latino-factsheet.pdf

16. Tables | Volume 33 | HIV Surveillance | Reports | Resource Library | HIV/AIDS | CDC. Published May 23, 2022. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance/vol-33/content/tables.html

17. Rangel MG, Martinez-Donate AP, Hovell M, et al. A TWO-WAY ROAD: RATES OF HIV INFECTION AND BEHAVIORAL RISK FACTORS AMONG DEPORTED MEXICAN LABOR MIGRANTS. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1630-1640. doi:10.1007/s10461-012-0196-z

18. HIV and Hispanic/Latino People in the U.S. | Fact Sheets | Newsroom | NCHHSTP | CDC. Published January 30, 2023. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/fact-sheets/hiv/hispanic-latino-factsheet.html

19. Kanamori M, De La Rosa M, Shrader CH, et al. Progreso en Salud: Findings from Two Adapted Social Network HIV Risk Reduction Interventions for Latina Seasonal Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(22):4530. doi:10.3390/ijerph16224530

20. Kinney S, Lea CS, Kearney G, Kinsey A, Amaya C. Predictors for Using a HIV Self-Test Among Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers in North Carolina. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(7):8348-8358. doi:10.3390/ijerph120708348

21. Kanamori M, De La Rosa M, Diez S, et al. A Brief Report: Lessons Learned and Preliminary Findings of Progreso en Salud, an HIV Risk Reduction Intervention for Latina Seasonal Farmworkers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(1):32. doi:10.3390/ijerph14010032

22. Sanchez M, Rojas P, Li T, et al. Evaluating a Culturally Tailored HIV Risk Reduction Intervention Among Latina Immigrants in the Farmworker Community: Latina Immigrant Farmworkers. WHM. 2016;8(3):245-262. doi:10.1002/wmh3.193

23. Organista KC. Towards a Structural-Environmental Model of Risk for HIV and Problem Drinking in Latino Labor Migrants: The Case of Day Laborers. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2007;16(1-2):95-125. doi:10.1300/J051v16n01_04

24. Painter T. Health Threats that Can Affect Hispanic/Latino Migrants and Immigrants IN New and Emerging Issues in Latinx Health. A. Martinez & S. Rhodes, eds. Springer. 2020, pp.169-195. In: ; 2020:169-195. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-24043-1_8

25. Haider S, Stoffel C, Donenberg G, Geller S. Reproductive Health Disparities: A Focus on Family Planning and Prevention Among Minority Women and Adolescents. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2(5):94-99. doi:10.7453/gahmj.2013.056

26. Mann L, Valera E, Hightow-Weidman LB, Barrington C. Migration and HIV risk: Life histories of Mexican-born men living with HIV in North Carolina. Cult Health Sex. 2014;16(7):820-834. doi:10.1080/13691058.2014.918282

27. Rhodes SD, Bischoff WE, Burnell JM, et al. HIV and sexually transmitted disease risk among male Hispanic/Latino migrant farmworkers in the Southeast: Findings from a pilot CBPR study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2010;53(10):976-983. doi:10.1002/ajim.20807

28. Bletzer KV. Risk and danger among women-who-prostitute in areas where farmworkers predominate. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17(2):251-278. doi:10.1525/maq.2003.17.2.251

29. Painter TM. Connecting the dots: when the risks of HIV/STD infection appear high but the burden of infection is not known--the case of male Latino migrants in the southern United States. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(2):213-226. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9220-0

30. McCoy HV, Shehadeh N, Rubens M, Navarro CM. Newcomer Status as a Protective Factor among Hispanic Migrant Workers for HIV Risk. Front Public Health. 2014;2:216. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00216

31. Smith SF, Acuna J, Feldman SR, et al. Tattooing practices in the migrant Latino farmworker population: Risk for blood-borne disease. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48(12):1400-1402. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03828.x

32. Albarrán CR, Nyamathi A. HIV and Mexican migrant workers in the United States: a review applying the vulnerable populations conceptual model. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care : JANAC. 2011;22(3):173-185. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2010.08.001