COVID-19 IMPACT ON AGRICULTURAL WORKERS

Note: NCFH typically relies on peer-reviewed research and government reports for its fact sheet series, but due to the urgent and constantly evolving nature of the pandemic, we have utilized reputable media sources as well.

Last updated: April 2023

Last updated: April 2023

Please see our COVID-19 and H-2A Guest Workers in the Southeastern U.S. fact sheet as well as our Farmworker Community COVID-19 Assessment Reports for more information on COVID-19 impact on Agricultural Workers.

INTRODUCTION

Agricultural worker populations are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 due to factors including lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), poor housing and working conditions, structural racism, discrimination, and barriers to health care. This fact sheet is updated quarterly to bring the most current information about the pandemic’s impact on agricultural workers.

COVID-19 PREVALENCE AMONG AGRICULTURAL WORKERS AND RURAL COMMUNITIES

DISPROPORTIONATE IMPACT

OCCUPATIONAL RISKS AND WORKING CONDITIONS ON U.S. FARMS

INTRODUCTION

Agricultural worker populations are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 due to factors including lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), poor housing and working conditions, structural racism, discrimination, and barriers to health care. This fact sheet is updated quarterly to bring the most current information about the pandemic’s impact on agricultural workers.

COVID-19 PREVALENCE AMONG AGRICULTURAL WORKERS AND RURAL COMMUNITIES

- As of February 6, 2023, there have been an estimated 690,000 COVID-19 cases among hired agricultural workers. The figure likely underestimates the number of cases since it excludes workers who are contracted and employed for temporary labor.1

- As of January 19, 2023, over 14 million cases of COVID-19 and 196,241 deaths from COVID-19 have been reported in nonmetropolitan counties. This is 14.1% of all U.S. cases and 18.2% of U.S. deaths reported at this time. The current prevalent case rate in nonmetropolitan counties is 3,043 cases per 10,000 residents and the current death rate is 42.58 per 10,000 residents. Both rates increased from previous data reported in October 2022. The prevalent case rate is currently lower in nonmetropolitan counties than metropolitan counties.2

DISPROPORTIONATE IMPACT

- Health Resources and Services Association (HRSA) Uniform Data System (UDS) data reports over 41,000 Migratory and Seasonal Agricultural Workers (MSAW) patients diagnosed with COVID-19 at Migrant Health Centers (MHC) in 2021. Among patients of MHCs in 2020 and 2021, COVID-19 test positivity was higher among MSAW patients than other patient demographics.3

- Research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that Hispanic or Latino workers employed in food production or agriculture have a substantially higher prevalence of COVID-19 compared to non-Hispanic workers in those industries. Among the 31 states that reported data, only 37% of workers in those industries were Hispanic or Latino but they represented 73% of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases in food processing and agriculture industries.4

- Hispanic persons are disproportionately affected by COVID-19, experiencing higher rates of hospitalization and death than White populations.5

- Underlying health conditions can increase the severity of the impact of the COVID-19 virus.6 For example, diabetes is a risk factor for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.3,5 Research suggests that agricultural workers have high rates of diabetes and obesity, with factors such as pesticide exposure increasing the odds of diabetes.7,8,9

- Social determinants of health, such as racism and discrimination, can lead to underlying health factors impacting the severity of COVID-19 cases.10 Agricultural workers report discrimination from employers based on their country of birth, legal status, and ability to speak English, that directly impacts their access to healthcare when injured.11 The anti-immigrant narrative can be a factor of discrimination in the United States.11,12

- Agricultural workers who speak Indigenous Mesoamerican languages lack access to translators, interpreters, or other resources within the U.S. health care system that could negatively impact their ability to access educational resources and care for COVID-19 related illness and prevention.13 This includes lack of interpretation of both testing results and medical recommendations.14

OCCUPATIONAL RISKS AND WORKING CONDITIONS ON U.S. FARMS

- As of 2021, there is no evidence of significant labor shortages in the agricultural labor industry due to the pandemic. H-2A contracts have increased during the pandemic and researchers predict continued expansion of the H-2A program in the future.15

- Latinx/Hispanic agricultural workers in California experience higher occupational stress due to the pandemic. In a study of 199 workers in Imperial County, approximately 40% reported statistically significant stress levels than before the pandemic. Foreign-born and elder respondents were more likely to experience this elevated stress. This study also found that Spanish speakers conducting COVID-19 outreach might have been effective for those workers with reported stress from language inequity.16

- Agricultural workers reported being fearful of losing their job after taking time off to access health services because employers threatened deportation or other retaliation to those who do take off work.17,18 In Central Florida in June 2021, from a study of 92 agricultural workers, 75% reported losing work hours due to the pandemic or lost work completely due to being let go by their employer.19

- Among 1,107 agricultural workers in Salinas Valley, California, 65% reported that their employer screened for fever and symptoms upon arrival at the workplace, which was recommended as part of a countywide agricultural advisory in 2020. There was a correlation between agricultural workers being screened for symptoms and temperature before work and a reduced risk of current infection.20

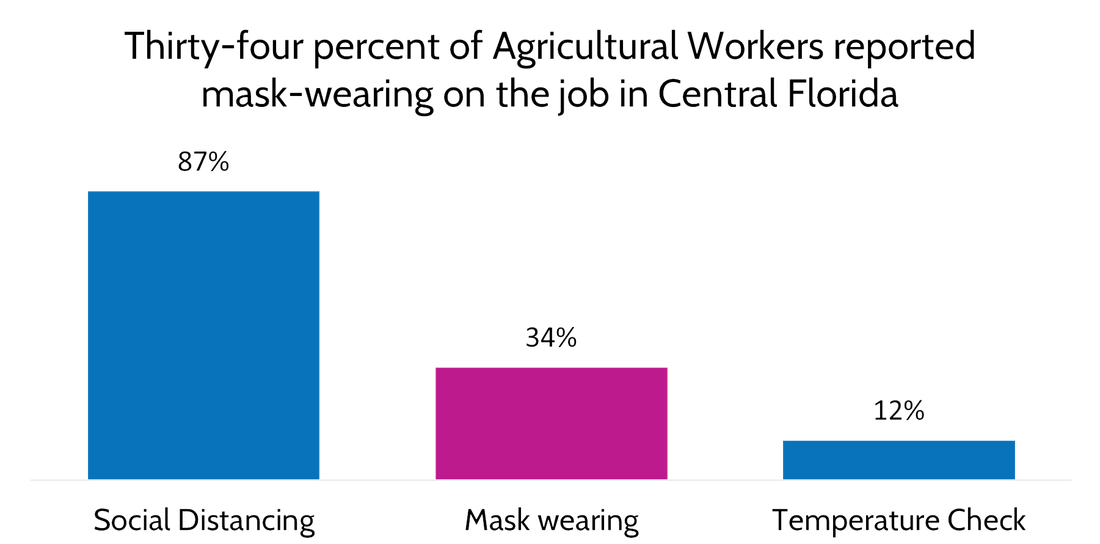

- Many agricultural workers are not able to keep a safe physical distance to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus in work environments. They work close to each other while harvesting and packing, and often ride together to and from work in buses or vans, increasing the risk for spread.19 Also, 40% of agricultural workers in Central Florida reported working with someone who was known to be infected with COVID-19 or had symptoms, within the last two weeks before the study in 2020.20 COVID-19 workplace safety precautions vary based on the employer. For example, out of the 92 agricultural workers in Florida, 87% of workers reported employer-enforced physical distancing, 34% reported mask-wearing, and 12% reported regular temperature checks.19 See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Thirty-four percent of Agricultural Workers reported mask-wearing on the job in Central Florida

Source: COVID-19 and Agricultural Workers: A Descriptive Study (2021)

Source: COVID-19 and Agricultural Workers: A Descriptive Study (2021)

- Instead of masks, agricultural workers tend to wear bandanas or scarves to mask their face because their employers don’t usually provide appropriate PPE and/or the surgical masks do not fair well in hot weather and intense labor conditions.21–24 Studies indicate that bandanas and neck gaiters are less efficient in reducing the spread of respiratory droplets.25

- Of the 339 H-2A workers surveyed, 78% reported their employer regularly provided face masks at work and 33% reported continuing to work while positive for COVID-19.26

HOUSING CONDITIONS AND RISK

ACCESS TO CARE

MENTAL HEALTH

PROMISING PRACTICES

COVID-19 VACCINATION GENERAL DATA

- Overcrowded and substandard housing conditions are a major concern for the potential of COVID-19 to spread through agricultural worker communities.27,28 A single building may house several dozen workers or more, who often sleep in dormitory-style quarters, making quarantining or physical distancing efforts difficult if not impossible. Limited access to restrooms and sinks, at home and in the field, may complicate hygiene prevention efforts.29

- Several states and counties provide funding for emergency quarantine housing for agricultural workers suffering from COVID-19. Other state and counties added funds to pay for lost wages or assistance with bills for agricultural workers affected by COVID-19 in 2020.26,27,28

ACCESS TO CARE

- In 2020, 21% of 1,105 agricultural workers surveyed across the United States reported having more difficulty accessing medical care or medicine since before the pandemic.38

- The COVID-19 Farmworker Survey (COFS) report found that agricultural workers who spoke Indigenous Mesoamerican languages were more likely to report lack of information and lack of sick leave, as well as having more difficulty paying for health care services than non-Indigenous language speaking agricultural worker respondents.23,24

MENTAL HEALTH

- Agricultural workers in 2020 reported being negatively impacted by the pandemic including symptoms of depression and/or anxiety.38

- In 2021, approximately 40% of 77 Latina agricultural workers reported stress scores that demonstrated clinical mental health concerns. Stressors included long work hours, bad weather, drug use by others, communicating in English, and balancing home and work life. 39 Qualitative data from the same study suggests that since participants and their coworkers received vaccines, stress about COVID-19 has reduced.39

- During the pandemic, female agricultural workers have reported more fear, worry, and anxiety than male agricultural workers. Risks for depression include being single living with children and separately having COVID-19 related symptoms.40

- During the pandemic, there has been revealed increased substance abuse by agricultural workers in California.40 Witnessing drug use of co-workers at the work or transportation site has also been noted as a source of stress for agricultural workers during the pandemic.16,39

PROMISING PRACTICES

- Isolating agricultural workers helped mitigate an outbreak in Iowa. In the summer of 2021, nine workers tested positive for COVID-19, including many who were asymptomatic. COVID-19 positive workers were isolated for 10 days with meals and hygiene products provided. Proteus Inc., a Migrant Health Voucher Program, conducted check in calls to assess health status. The workers returned to work after isolation and no additional positive cases occurred during that harvest season.41

- Working and communicating with the employer was essential to identify positive cases among H-2A workers and to isolate workers to prevent future outbreaks. Using Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) funding, Proteus Inc. safely transported 170 workers from Mexico to Iowa with a process that kept workers in travel cohorts, tracked close contacts, and set up isolation procedures upon arrival. The model produced a 3.5% positivity rate compared to a 12.7% positivity rate in previous H-2A worker transportation on the same farm. During transportation, workers were assigned a bus and a seat and required to wear masks. Workers received a PCR test upon arrival and those with a positive result were isolated for 10 days in employer-provided housing. Workers in isolation were medically evaluated via telehealth and were delivered medicine as needed. Close contact of workers that tested positive were also isolated, tested regularly, and released seven days post exposure if they tested negative.42

COVID-19 VACCINATION GENERAL DATA

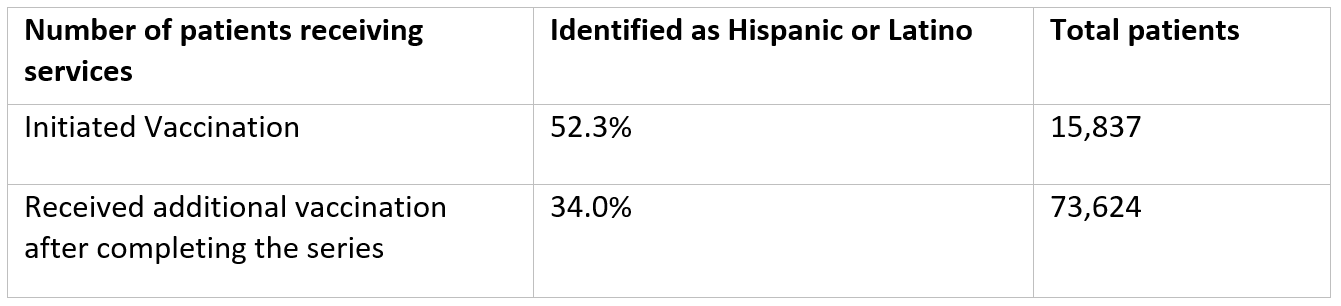

- Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) conducts a bi-weekly survey of Health Centers. The data represent a two-week reporting period. Data available from January 19, 2023, indicated that 1,015 (74% of total) Health Centers responded. Out of 15,837 patients initiating vaccination during those previous two weeks, 52.3% self-identified as Hispanic or Latino (not including those reporting “one or more race”). Out of 73,624 patients who received additional vaccinations after completing the series, 23.9% self-identified as Hispanic or Latino (not including those who reported “one or more race”).43 See Table 1 below.

Table 1: Patients Receiving Vaccine Services at Health Centers, January 19, 2023

Source: HRSA bi-weekly surveys https://bphc.hrsa.gov/emergency-response/coronavirus-health-center-data

Source: HRSA bi-weekly surveys https://bphc.hrsa.gov/emergency-response/coronavirus-health-center-data

- Forty-eight percent of those who received oral antiviral medication from these Health Centers self-identified as Racial and/or Ethnic Minority patients, and about 2.4% identified as migratory agricultural workers.43

- As part of the Health Center COVID-19 Vaccine Program, over 9 million vaccinations have been administered from February 26, 2021, to current time. Approximately 76.15% of those patients self-identified as a racial and/or ethnic minority (including Hispanic/Latino).40

COVID-19 VACCINATION AMONG AGRICULTURAL WORKERS

- Uniform Data System (UDS) reports show Migrant Health Centers administered the COVID-19 vaccine to 121,733 patients in 2021.3

- Farmworker COVID-19 Community Assessments (FCCA) data showed 94% of H-2A workers surveyed in Georgia and North Carolina in 2022 were fully vaccinated and 41% reported having received a booster shot.26

- In July 2021, a follow-up research study of 81 agricultural workers in Central Florida, 53% respondents reported receiving a COVID-19 vaccine, (48% had completed the series and 5% were partially vaccinated). Among the 15% originally unwilling to receive a vaccine in June of 2020, 67% had received at least one dose.19

- In March 2022, 273 agricultural workers were surveyed in Colquitt County, Georgia and 72% reported being fully vaccinated. Twenty-eight percent had also received a booster dose.33,45

- In May 2022, 249 agricultural workers were surveyed in Weld, Colorado and 72% reported being fully vaccinated. Thirty-two percent of respondents also received at least one booster dose. Most of the 195 who reported the location of their first dose received noted it was at a U.S. Community/Migrant Health Center.46,45

- Out of 335 agricultural workers surveyed in Sampson County, North Carolina in April 2022, 81% said they were fully vaccinated, and 29% of respondents received at least one booster dose as well.47,45

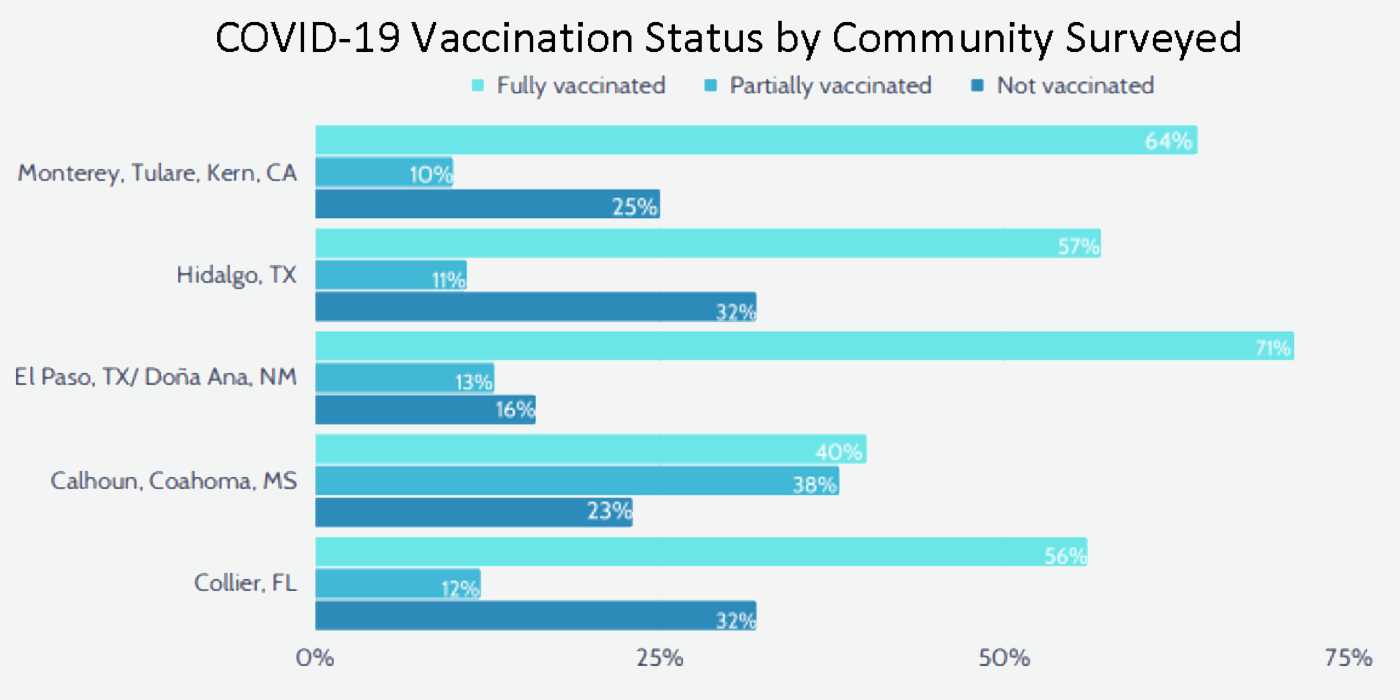

- In 2021, 1,094 surveys were conducted with agricultural workers in five communities to assess COVID-19 impact. COVID-19 vaccination coverage varied by community (see Figure 3), however the percentage of respondents that were fully vaccinated was lower than the general population county vaccination rate at the same time in four out of the five communities.48

*Fully vaccinated includes respondents who received one dose of the Janssen/Johnson and Johnson vaccine or two doses of any COVID-19 vaccine approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the World Health Organization. Partially vaccinated respondents include those who received one dose of a two-dose FDA- or WHO-approved vaccine, and those who received an unapproved vaccine. Not vaccinated respondents did not receive any COVID-19 vaccine.

Figure 3: COVID-19 Vaccination Status by Community Surveyed in August - December 2021

Source: Farmworker Covid-19 Community Assessments Executive Summary

Source: Farmworker Covid-19 Community Assessments Executive Summary

CONCERNS ABOUT VACCINES

- In a 2020 – 2021 qualitative study with 55 Latinx and Indigenous Mexican agricultural workers in Coachella Valley, researchers found that misinformation, lack of trust in institutions and insecurity around employment and immigration status impacted participants perceptions of the COVID-19 virus, testing, and vaccination.49

- In a 2021 qualitative study, researchers conducted 22 interviews with Latinx mothers in agricultural worker communities in Oregon in which participants spoke positively about COVID-19 vaccines as it related to their ability to protect their families.

- Side effects from and mistrust in the vaccine were primary concerns impacting agricultural workers’ decision to get vaccinated.19,33

Disclaimer: This publication is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $435,561 with 0% financed with nongovernmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

REFERENCES

1. Food & Ag Vulnerability Index. Purdue University - College of Agriculture. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://ag.purdue.edu/department/agecon/foodandagvulnerabilityindex.html

2. Ullrich F, Mueller K. Confirmed COVID-19 Cases, Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Counties. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://rupri.public-health.uiowa.edu/publications/policybriefs/2020/COVID%20Data%20Brief.pdf

3. Whitsett K. A Profile of Migrant Health 2021 Uniform Data System Analysis - Unpublished.

4. Waltenburg MA, Rose CE, Victoroff T, et al. Early Release - Coronavirus Disease among Workers in Food Processing, Food Manufacturing, and Agriculture Workplaces - Volume 27, Number 1—January 2021 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. doi:10.3201/eid2701.203821

5. CDC. Racism and Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published April 8, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/racism-disparities/impact-of-racism.html

6. CDC. COVID-19 and Your Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

7. Moyce S, Hernandez K, Schenker M. Diagnosed and Undiagnosed Diabetes among Agricultural Workers in California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(4):1289-1301. doi:10.1353/hpu.2019.0102

8. Curl CL, Spivak M, Phinney R, Montrose L. Synthetic Pesticides and Health in Vulnerable Populations: Agricultural Workers. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2020;7(1):13-29. doi:10.1007/s40572-020-00266-5

9. Starling AP, Umbach DM, Kamel F, Long S, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA. Pesticide use and incident diabetes among wives of farmers in the Agricultural Health Study. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(9):629-635. doi:10.1136/oemed-2013-101659

10. Handal AJ, Iglesias-Ríos L, Fleming PJ, Valentín-Cortés MA, O’Neill MS. “Essential” but Expendable: Farmworkers During the COVID-19 Pandemic—The Michigan Farmworker Project. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(12):1760-1762. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305947

11. Snipes SA, Cooper SP, Shipp EM. “The Only Thing I Wish I Could Change Is That They Treat Us Like People and Not Like Animals”: Injury and Discrimination Among Latino Farmworkers. Journal of Agromedicine. 2017;22(1):36-46. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2016.1248307

12. Terrazas SR, McCormick A. Coping Strategies That Mitigate Against Symptoms of Depression Among Latino Farmworkers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2018;40(1):57-72. doi:10.1177/0739986317752923

13. Maxwell AE, Young S, Moe E, Bastani R, Wentzell E. Understanding factors that influence health care utilization among Mixtec and Zapotec women in a farmworker community in California. J Community Health. 2018;43(2):356-365. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0430-8

14. Facebook, Twitter, options S more sharing, et al. Op-Ed: Indigenous farmworkers are being hit by COVID myths — and deaths. Los Angeles Times. Published December 27, 2021. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2021-12-27/covid-indigenous-farmworkers

15. Hill AE, Martin P, eds. COVID-19 and Farm Workers.; 2021. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.311308

16. Keeney AJ, Quandt A, Villaseñor MD, Flores D, Flores L. Occupational Stressors and Access to COVID-19 Resources among Commuting and Residential Hispanic/Latino Farmworkers in a US-Mexico Border Region. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(2):763. doi:10.3390/ijerph19020763

17. Prado JB, Mulay PR, Kasner EJ, Bojes HK, Calvert GM. Acute Pesticide-Related Illness Among Farmworkers: Barriers to Reporting to Public Health Authorities. J Agromedicine. 2017;22(4):395-405. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2017.1353936

18. Liebman AK, Juarez-Carrillo PM, Reyes IAC, Keifer MC. Immigrant dairy workers’ perceptions of health and safety on the farm in America’s Heartland. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2016;59(3):227-235. doi:10.1002/ajim.22538

19. Chicas R, Xiuhtecutli N, Houser M, et al. COVID-19 and Agricultural Workers: A Descriptive Study. J Immigrant Minority Health. Published online October 12, 2021. doi:10.1007/s10903-021-01290-9

20. Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection among farmworkers in Monterey County, California | medRxiv. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.01.21250963v1

21. Farmworkers are getting coronavirus. They face retaliation for demanding safe conditions. The World from PRX. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://theworld.org/stories/2020-07-29/sick-covid-19-farmworkers-face-retaliation-demanding-safe-conditions

22. Coleman ML. Essential Workers Are Being Treated as Expendable. The Atlantic. Published April 23, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/farmworkers-are-being-treated-as-expendable/610288/

23. Saxton D, Villarejo D, DeLeon E, Blanco S, Martinez L. AND A WIDE RANGE OF RESEARCHERS AND PARTNERS: :51.

24. COFS-_Phase-Two-Preliminary-Report.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2022. https://cirsinc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/COFS-_Phase-Two-Preliminary-Report.pdf

25. Why Scarfs, Bandanas, or Gaiters Are Not Used as Masks or Face Coverings at Southwest Tech | Southwest Tech News. Published October 16, 2020. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.swtc.edu/news/covid-19-coronavirus/mask-wearing/why-scarfs-bandanas-or-gaiters-are-not-considered-masks/

26. COVID-19 and H-2A Workers Fact Sheet. NATIONAL CENTER FOR FARMWORKER HEALTH. Accessed February 6, 2023. http://www.ncfh.org/covid-19-and-h-2a-workers-fact-sheet.html

27. Arcury TA, Weir M, Chen H, et al. Migrant farmworker housing regulation violations in North Carolina. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2012;55(3):191-204. doi:10.1002/ajim.22011

28. Quandt S, Brooke C, Fagan K, Howe A, Thornburg T, McCurdy S. Farmworker Housing in the United States and Its Impact on Health. New Solutions. 2015;25(3):263-286.

29. Pena A, Teather-Posadas E. Field Sanitation in U.S. Agriculture: Evidence from NAWS and Future Data Needs. Journal of Agromedicine. 2018;23(2). Accessed April 22, 2020. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1059924X.2018.1427642

30. Plevin R. Riverside County to consider providing housing, financial aid to farmworkers with COVID-19. The Desert Sun. Published August 25, 2020. Accessed August 25, 2020. https://www.desertsun.com/story/news/2020/08/21/riverside-county-could-provide-housing-financial-aid-farmworkers-covid-19/3413200001/

31. Melton J. FHDC Provides Support for Two New Oregon Worker Relief Funds. Published August 25, 2020. Accessed August 25, 2020. http://fhdc.org/2020/08/fhdc-provides-support-for-two-new-oregon-worker-relief-funds/

32. Farmworker Household Assistance Program (FHAP). Ventura County Community Foundation. Published August 25, 2020. Accessed August 25, 2020. https://vccf.org/fhap/

33. Colquitt Count, GA Rapid Assessment. Accessed February 6, 2023. http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/colquitt_ga_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2022.pdf

34. Collier County Florida Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed February 6, 2023 http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/collier_county_florida_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2021_.pdf

35. El Paso County TX and Dona Ana County NM Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed February 6, 2023 http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/el_paso_county_tx_and_dona_ana_county_nm_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2021.pdf

36. Mississippi Counties Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed February 6, 2023 http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/ms_community_profile_-_fcca_survey_report_2021.pdf

37. Hidalgo County, TX Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed February 6, 2023 http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/hidalgo_county_tx_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2021.pdf

38. Mora AM, Lewnard JA, Kogut K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Vaccine Hesitancy among Farmworkers from Monterey County, California. Published online December 22, 2020:2020.12.18.20248518. doi:10.1101/2020.12.18.20248518

39. Keeney AJ, Quandt A, Flores D, Flores L. Work-Life Stress during the Coronavirus Pandemic among Latina Farmworkers in a Rural California Region. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(8):4928. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084928

40. Mora AM, Lewnard JA, Rauch S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on California Farmworkers’ Mental Health and Food Security. Journal of Agromedicine. 2022;27(3):303-314. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2022.2058664

41. Corwin C, Sinnwell E, Culp K. A Mobile Primary Care Clinic Mitigates an Early COVID-19 Outbreak Among Migrant Farmworkers in Iowa. Journal of Agromedicine. 2021;26(3):346-351. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2021.1913272

42. Johnson C, Dukes K, Sinnwell E, Culp K, Zinnel D, Corwin C. Innovative Cohort Process to Minimize COVID-19 Infection for Migrant Farmworkers During Travel to Iowa. Workplace Health Saf. 2022;70(1):17-23. doi:10.1177/21650799211045308

43. Health Center COVID-19 Survey. Bureau of Primary Health Care. Published April 8, 2020. Accessed February 6, 2023 https://bphc.hrsa.gov/emergency-response/coronavirus-health-center-data

44. Health Center COVID-19 Vaccinations Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Patients. Accessed February 6, 2023 https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-centers/covid-vaccination

45. FCCA - NATIONAL CENTER FOR FARMWORKER HEALTH. Accessed November 8, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/fcca.html

46. Weld County Co Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed October 25, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/weld_co_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2022-1.pdf

47. Sampson County, NC Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed October 25, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/sampson_nc_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2022.pdf

48. Farmworker Community Covid Assessment FCCA Executive Summary. NATIONAL CENTER FOR FARMWORKER HEALTH. Accessed March 25, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/fcca.html

49. Gehlbach D, Vázquez E, Ortiz G, et al. Perceptions of the Coronavirus and COVID-19 testing and vaccination in Latinx and Indigenous Mexican immigrant communities in the Eastern Coachella Valley. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1019. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13375-7

50. California Counties Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed October 19, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/monterey_kern_tulare_cali_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2021.pdf

REFERENCES

1. Food & Ag Vulnerability Index. Purdue University - College of Agriculture. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://ag.purdue.edu/department/agecon/foodandagvulnerabilityindex.html

2. Ullrich F, Mueller K. Confirmed COVID-19 Cases, Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Counties. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://rupri.public-health.uiowa.edu/publications/policybriefs/2020/COVID%20Data%20Brief.pdf

3. Whitsett K. A Profile of Migrant Health 2021 Uniform Data System Analysis - Unpublished.

4. Waltenburg MA, Rose CE, Victoroff T, et al. Early Release - Coronavirus Disease among Workers in Food Processing, Food Manufacturing, and Agriculture Workplaces - Volume 27, Number 1—January 2021 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC. doi:10.3201/eid2701.203821

5. CDC. Racism and Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published April 8, 2021. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/racism-disparities/impact-of-racism.html

6. CDC. COVID-19 and Your Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

7. Moyce S, Hernandez K, Schenker M. Diagnosed and Undiagnosed Diabetes among Agricultural Workers in California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(4):1289-1301. doi:10.1353/hpu.2019.0102

8. Curl CL, Spivak M, Phinney R, Montrose L. Synthetic Pesticides and Health in Vulnerable Populations: Agricultural Workers. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2020;7(1):13-29. doi:10.1007/s40572-020-00266-5

9. Starling AP, Umbach DM, Kamel F, Long S, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA. Pesticide use and incident diabetes among wives of farmers in the Agricultural Health Study. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(9):629-635. doi:10.1136/oemed-2013-101659

10. Handal AJ, Iglesias-Ríos L, Fleming PJ, Valentín-Cortés MA, O’Neill MS. “Essential” but Expendable: Farmworkers During the COVID-19 Pandemic—The Michigan Farmworker Project. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(12):1760-1762. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305947

11. Snipes SA, Cooper SP, Shipp EM. “The Only Thing I Wish I Could Change Is That They Treat Us Like People and Not Like Animals”: Injury and Discrimination Among Latino Farmworkers. Journal of Agromedicine. 2017;22(1):36-46. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2016.1248307

12. Terrazas SR, McCormick A. Coping Strategies That Mitigate Against Symptoms of Depression Among Latino Farmworkers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2018;40(1):57-72. doi:10.1177/0739986317752923

13. Maxwell AE, Young S, Moe E, Bastani R, Wentzell E. Understanding factors that influence health care utilization among Mixtec and Zapotec women in a farmworker community in California. J Community Health. 2018;43(2):356-365. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0430-8

14. Facebook, Twitter, options S more sharing, et al. Op-Ed: Indigenous farmworkers are being hit by COVID myths — and deaths. Los Angeles Times. Published December 27, 2021. Accessed January 7, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2021-12-27/covid-indigenous-farmworkers

15. Hill AE, Martin P, eds. COVID-19 and Farm Workers.; 2021. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.311308

16. Keeney AJ, Quandt A, Villaseñor MD, Flores D, Flores L. Occupational Stressors and Access to COVID-19 Resources among Commuting and Residential Hispanic/Latino Farmworkers in a US-Mexico Border Region. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(2):763. doi:10.3390/ijerph19020763

17. Prado JB, Mulay PR, Kasner EJ, Bojes HK, Calvert GM. Acute Pesticide-Related Illness Among Farmworkers: Barriers to Reporting to Public Health Authorities. J Agromedicine. 2017;22(4):395-405. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2017.1353936

18. Liebman AK, Juarez-Carrillo PM, Reyes IAC, Keifer MC. Immigrant dairy workers’ perceptions of health and safety on the farm in America’s Heartland. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2016;59(3):227-235. doi:10.1002/ajim.22538

19. Chicas R, Xiuhtecutli N, Houser M, et al. COVID-19 and Agricultural Workers: A Descriptive Study. J Immigrant Minority Health. Published online October 12, 2021. doi:10.1007/s10903-021-01290-9

20. Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection among farmworkers in Monterey County, California | medRxiv. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.01.21250963v1

21. Farmworkers are getting coronavirus. They face retaliation for demanding safe conditions. The World from PRX. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://theworld.org/stories/2020-07-29/sick-covid-19-farmworkers-face-retaliation-demanding-safe-conditions

22. Coleman ML. Essential Workers Are Being Treated as Expendable. The Atlantic. Published April 23, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/farmworkers-are-being-treated-as-expendable/610288/

23. Saxton D, Villarejo D, DeLeon E, Blanco S, Martinez L. AND A WIDE RANGE OF RESEARCHERS AND PARTNERS: :51.

24. COFS-_Phase-Two-Preliminary-Report.pdf. Accessed October 17, 2022. https://cirsinc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/COFS-_Phase-Two-Preliminary-Report.pdf

25. Why Scarfs, Bandanas, or Gaiters Are Not Used as Masks or Face Coverings at Southwest Tech | Southwest Tech News. Published October 16, 2020. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://www.swtc.edu/news/covid-19-coronavirus/mask-wearing/why-scarfs-bandanas-or-gaiters-are-not-considered-masks/

26. COVID-19 and H-2A Workers Fact Sheet. NATIONAL CENTER FOR FARMWORKER HEALTH. Accessed February 6, 2023. http://www.ncfh.org/covid-19-and-h-2a-workers-fact-sheet.html

27. Arcury TA, Weir M, Chen H, et al. Migrant farmworker housing regulation violations in North Carolina. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2012;55(3):191-204. doi:10.1002/ajim.22011

28. Quandt S, Brooke C, Fagan K, Howe A, Thornburg T, McCurdy S. Farmworker Housing in the United States and Its Impact on Health. New Solutions. 2015;25(3):263-286.

29. Pena A, Teather-Posadas E. Field Sanitation in U.S. Agriculture: Evidence from NAWS and Future Data Needs. Journal of Agromedicine. 2018;23(2). Accessed April 22, 2020. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1059924X.2018.1427642

30. Plevin R. Riverside County to consider providing housing, financial aid to farmworkers with COVID-19. The Desert Sun. Published August 25, 2020. Accessed August 25, 2020. https://www.desertsun.com/story/news/2020/08/21/riverside-county-could-provide-housing-financial-aid-farmworkers-covid-19/3413200001/

31. Melton J. FHDC Provides Support for Two New Oregon Worker Relief Funds. Published August 25, 2020. Accessed August 25, 2020. http://fhdc.org/2020/08/fhdc-provides-support-for-two-new-oregon-worker-relief-funds/

32. Farmworker Household Assistance Program (FHAP). Ventura County Community Foundation. Published August 25, 2020. Accessed August 25, 2020. https://vccf.org/fhap/

33. Colquitt Count, GA Rapid Assessment. Accessed February 6, 2023. http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/colquitt_ga_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2022.pdf

34. Collier County Florida Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed February 6, 2023 http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/collier_county_florida_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2021_.pdf

35. El Paso County TX and Dona Ana County NM Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed February 6, 2023 http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/el_paso_county_tx_and_dona_ana_county_nm_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2021.pdf

36. Mississippi Counties Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed February 6, 2023 http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/ms_community_profile_-_fcca_survey_report_2021.pdf

37. Hidalgo County, TX Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed February 6, 2023 http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/hidalgo_county_tx_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2021.pdf

38. Mora AM, Lewnard JA, Kogut K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Vaccine Hesitancy among Farmworkers from Monterey County, California. Published online December 22, 2020:2020.12.18.20248518. doi:10.1101/2020.12.18.20248518

39. Keeney AJ, Quandt A, Flores D, Flores L. Work-Life Stress during the Coronavirus Pandemic among Latina Farmworkers in a Rural California Region. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(8):4928. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084928

40. Mora AM, Lewnard JA, Rauch S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on California Farmworkers’ Mental Health and Food Security. Journal of Agromedicine. 2022;27(3):303-314. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2022.2058664

41. Corwin C, Sinnwell E, Culp K. A Mobile Primary Care Clinic Mitigates an Early COVID-19 Outbreak Among Migrant Farmworkers in Iowa. Journal of Agromedicine. 2021;26(3):346-351. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2021.1913272

42. Johnson C, Dukes K, Sinnwell E, Culp K, Zinnel D, Corwin C. Innovative Cohort Process to Minimize COVID-19 Infection for Migrant Farmworkers During Travel to Iowa. Workplace Health Saf. 2022;70(1):17-23. doi:10.1177/21650799211045308

43. Health Center COVID-19 Survey. Bureau of Primary Health Care. Published April 8, 2020. Accessed February 6, 2023 https://bphc.hrsa.gov/emergency-response/coronavirus-health-center-data

44. Health Center COVID-19 Vaccinations Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Patients. Accessed February 6, 2023 https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-centers/covid-vaccination

45. FCCA - NATIONAL CENTER FOR FARMWORKER HEALTH. Accessed November 8, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/fcca.html

46. Weld County Co Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed October 25, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/weld_co_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2022-1.pdf

47. Sampson County, NC Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed October 25, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/sampson_nc_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2022.pdf

48. Farmworker Community Covid Assessment FCCA Executive Summary. NATIONAL CENTER FOR FARMWORKER HEALTH. Accessed March 25, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/fcca.html

49. Gehlbach D, Vázquez E, Ortiz G, et al. Perceptions of the Coronavirus and COVID-19 testing and vaccination in Latinx and Indigenous Mexican immigrant communities in the Eastern Coachella Valley. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1019. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13375-7

50. California Counties Rapid Assessment Report. Accessed October 19, 2022. http://www.ncfh.org/uploads/3/8/6/8/38685499/monterey_kern_tulare_cali_rapid_assessment_-_survey_report_2021.pdf

Return to main Fact Sheets & Research page