Dairy Workers

Last updated: October 2014

Click Here to download the fact sheet as a PDF file.

The Public Health Service Act provides the definition of migratory and seasonal agricultural workers for health center grantees, and includes those working in aquaculture and animal production provided the patient meets the guidelines for being a migratory or seasonal worker. The Uniform Data System Manual, the reporting mechanism for all health centers, states “For both [migratory and seasonal] categories of workers, the term agriculture means farming in all its branches as defined by the OMB-developed North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), and includes seasonal workers included in the following codes and all sub-codes within: 111, 112, 1151, and 1152”, removing a previous exclusion of animal productions workers.[1]

This change increases the potential number of agricultural worker patients a Health Center may serve, and this subpopulation of agricultural workers has a unique set of social, economic, and occupational health risks and disparities. While many dairy workers would not be classified as agricultural workers because their work is year-round, some may hold seasonal or temporary jobs and will thus need to be classified as agricultural workers. Temporary dairy farm jobs may be more common in areas where dairy production is unstable due to market forces and in regions where dairy production slows during the summer months.[2]

WORKER DEMOGRAPHICS

- According to Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 94,327 workers in 6,813 dairy cattle and milk production establishments (NAICS code 11212) reported in 2012 throughout the U.S. An additional 14,355 worked in 1,081 cattle feedlots during 2012 (NAICS code 112112).[3]

- A survey of 2,000 dairy farms in 2009 found that of the 138,000 full-time workers, 41% were foreign-born.[4]

- Dairy cattle and milk production workers earned an average of $554 per week in 2012, and cattle feedlot workers earned an average of $743 per week. This is higher than the average pay of $522 per week for crop production workers during the same year.[5]

- Dairy workers are often recent immigrants and have limited English proficiency. A survey of 111 Hispanic dairy workers in New York indicated that one-fourth of workers emigrated from Guatemala, and three-fourths from Mexico, with the majority of workers being young, male, and uneducated.[6] A 2009 survey of the rapidly growing southern Idaho dairy industry found that the majority of workers were Hispanic, and were often males travelling alone.[7]

- Many dairy workers migrate for work and hold temporary jobs. Migration and length of employment is often dependent on the region and the family structure of the worker. A Migrant Education study in Vermont found that of 413 migratory students who worked and travelled on their own, the average length of employment at a single establishment was 12.3 months. Dairy worker parents of migratory students remained at a single place of establishment for an average of 22.5 months, indicating that families migrate less frequently than those migrating without families.[8] In addition, 60% of Migrant Education students in Vermont originated from Mexico, with the largest percentage (39%) emigrating from the state of Chiapas.

- Dairy production is becoming increasingly concentrated and large-scale globally. The European Union produces the most dairy of any region, but the U.S. has the largest dairy production establishments.[9]

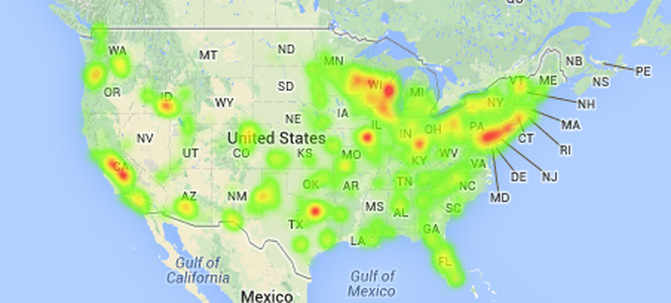

The map below is a heat map demonstrating the concentrations of dairy farm locations in the USA, with red areas possessing greater numbers of dairy farm employees.[10]

LABOR CONDITIONS

- Dairy workers labor long hours for low wages. A survey of 111 Hispanic dairy workers in New York found that dairy workers worked an average of 62 hours per week, with an average hourly wage of $7.51.[11]

- Dirty working conditions coupled with long hours, no overtime pay, and physically demanding work create an environment that creates un-empowered workers, and labor organization is often difficult.[12]

- A survey of 60 dairy workers in New Mexico in 2012 found that 85% worked six or more days per week, half worked more than eight hours a day, and a third of workers never received lunch breaks.[13]

- Unventilated establishments expose workers to manure dust, bacteria, and other particulates that can damage respiratory passages and lead to airway obstruction.[14]

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH & HEALTH CARE ACCESS

- The non-fatal injury rate among workers in dairy cattle and milk production in 2012 was 5.6 injuries per 100 full-time workers and 14.6 illnesses per 100,000 full-time workers. The total injury and illness rate was 5.7 per 100 full-time workers, compared to the private industry average of 3.4.[15] Thirty-five workers in this industry died due to work-related incidents in 2012.

- Workers regularly exposed to cattle infected with tuberculosis have been shown to be at higher risk for contracting latent and active tuberculosis, as bovine tuberculosis can also infect humans. A study conducted in 2013 demonstrated that dairy workers had more than twice the risk of testing positive for tuberculosis as compared to non-dairy workers, and that over half of the 311 dairy workers tested positive for latent tuberculosis.[16]

- Dairy workers with tasks in the milking parlor had more than five times risk of carpal tunnel syndrome as compared to dairy workers with non-milking tasks, indicating that occupational risks and exposures vary greatly in the dairy industry, even with the same establishment.[17]

- Musculoskeletal injuries are common among dairy parlor workers. A cross-sectional study of 452 dairy parlor workers found that 76% had at least one body part affected by an occupationally related musculoskeletal injury, most commonly in an upper extremity.[18]

- A survey of 120 Hispanic dairy workers in Vermont found that fear of immigration enforcement was the greatest barrier to receiving health care, and workers reported that musculoskeletal pain and oral and mental health were major health concerns.[19]

- Among 60 dairy workers surveyed in New Mexico, 88% did not have any form of health insurance, and 20% of those who experienced a work-related injury and needed medical care reported never receiving any medical attention.[20]

- Employers may struggle with implementing general health and safety training in a largely Spanish-speaking workforce and many dairy farms are located in rural areas with few professional interpreters. However, implementation of limited community-based participatory training programs and community health worker programs have been shown to improve worker health and safety knowledge.[21]

REFERENCES

[1] Bureau of Primary Health Care, Health Resources and Services Administration. (2013). BPHC Uniform Data System Manual 2013. Retrieved from http://bphc.hrsa.gov/healthcenterdatastatistics/reporting/2013udsreport.pdf

[2] Bent, M. (2011). A land of milk and honey: Dairy farms, H-2A workers, and change on the horizon. Vermont Law Review, 35:741-764. Retrieved from http://lawreview.vermontlaw.edu/files/2012/02/15-Bent-Proof.pdf

[3] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor. (2014). Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages [query based on U.S. totals, NAICS codes 112112, 11212, all private establishments]. Retrieved 10 Mar 2014 from http://www.bls.gov/data/

[4] Rosson, P., Adcock, F., Susanto, D., & Anderson, D. (2009). The economic impacts of immigration on U.S. dairy farms. Retrieved from http://www.nmpf.org/sites/default/files/NMPF%20Immigration%20Survey%20Web.pdf

[5] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor. (2014). Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages [query based on U.S. totals, NAICS codes 112112, 11212, all private establishments]. Retrieved 10 Mar 2014 from http://www.bls.gov/data/

[6] Maloney, T.R., & Grusenmeyer, D.C. (2005). Survey of Hispanic dairy workers in New York State. Retrieved from http://vivo.cornell.edu/display/individual16566

[7] Salant, P., Wulfhorst, J.D., Kane, S., & Dearien, C. (2009). Community level impacts of Idaho’s changing dairy industry. Retreived from http://icha.idaho.gov/docs/Uof%20I%20Dairy%20Report%20Community_Level_Impacts(10_13_09).pdf

[8] Shea, E. (2009). Migrant labor turnover among dairy farm workers: Insights from the Vermont Migrant Education Program. Retrieved from http://www.uvm.edu/extension/agriculture/faccp/files/research/migrant_labor_turnover.pdf

[9] Douphrate DI, Hagevoort GR, Nonnenmann MW, Lunner Kolstrup C, Reynolds SJ, Jakob M & Kinsel M. (2013). The dairy industry: A brief description of production practices, trends, and farm characteristics around the world. Journal of Agromedicine, 18(3):187-97. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2013.796901.

[10] References USA. (n.d.). Heat map: Minor industry group 0241, dairy farms. Retrieved 18 March 2014 from http://0-www.referenceusa.com.sapl.sat.lib.tx.us/UsBusiness/HeatMap/20c1d7606b374a56a5729ff358e23f4c

[11] Maloney, T.R., & Grusenmeyer, D.C. (2005). Survey of Hispanic dairy workers in New York State. Retrieved from http://vivo.cornell.edu/display/individual16566

[12] Clarren, R. (31 August 2009). The dark side of dairies. High Country News. Retrieved from https://www.hcn.org/issues/41.15/the-dark-side-of-dairies/article_view?searchterm=dark%20side%20of%20dairies&b_start:int=0

[13] New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty. (2012). Human rights alert: New Mexico’s invisible and downtrodden workers. Retrieved from http://www.fronterasdesk.org/sites/default/files/field/docs/2013/07/Report-FINAL-PDF-2013-06-28_0.pdf

[14] Eastman C., Schenker M.B., Mitchell D.C., Tancredi D.J., Bennett D.H., & Mitloehner F.M. (2013). Acute pulmonary function change associated with work on large dairies in California. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55(1): 74-9. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318270d6e4

[15] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor. (2014). Occupational injuries/illnesses and fatal injuries profiles [query fro NAICS code 11212). Retrieved 10 Mar 2014 from http://www.bls.gov/data/#injuries

[16] Torres-Gonzalez P., Soberanis-Ramos O., Martinez-Gamboa A., Chavez-Mazari B., Barrios-Herrera M.T., Torres-Rojas M., Cruz-Hervert L.P., Garcia-Garcia L.,Singh M., Gonzalez-Aguirre A., Ponce de Leon-Garduño A., Sifuentes-Osornio J., & Bobadilla-Del-Valle M. (2013). Prevalence of latent and active tuberculosis among dairy farm workers exposed to cattle infected by Mycobacterium bovis. PLos Neglected Tropical Diseases, 7(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002177

[17] Patil, A., Rosecrance, J., Douphrate, D., & Gilkey, D. (2012). Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome among dairy workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 55(2): 127-35. doi: 10.1002/ajim.21995

[18] Douphrate D.I., Gimeno D., Nonnenmann M.W., Hagevoort R., Rosas-Goulart C., & Rosecrance J.C. (2014). Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal symptoms among US large-her dairy parlor workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 57(3): 370-9. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22286

[19] Baker, D., & Chappelle, D. (2012). Health status and needs of Latino dairy farmworkers in Vermont. Journal of Agromedicine, 17(3): 277-87. DOI: 10.1080/1059924X.2012.686384

[20] New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty. (2012). Human rights alert: New Mexico’s invisible and downtrodden workers. Retrieved from http://www.fronterasdesk.org/sites/default/files/field/docs/2013/07/Report-FINAL-PDF-2013-06-28_0.pdf

[21] Arcury, T.A., Estrada, J.M., & Quandt, S.A. (2010). Overcoming language and literacy barriers in safety and health training of agricultural workers. Journal of Agromedicine, 15(3): 236-48. DOI: 10.1080/1059924X.2010.486958

Agricultural Worker Factsheets are published by the National Center for Farmworker Health, Inc. 1770 FM 967, Buda, TX 7861 0, (512) 312-2700. This publication was made possible through grant number U30CS0 9737 from the Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Primary Health Care, and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of HRSA.