H-2A GUEST WORKER FACT SHEET

Last updated October 2020.

Download the PDF version of this fact sheet.

Download the PDF version of this fact sheet.

BACKGROUND ON THE H-2 VISA PROGRAM

The H-2 visa program allows immigrants to temporarily work and reside in the U.S. to fulfill labor needs in certain industries that experience labor shortages, such as agriculture.[1,2] The H-2 visa program traces its beginnings to the Bracero program, a temporary immigrant farm labor program that began during World War II, and became legally official in 1952 in the Immigration and Nationality Act.[2,3] The program was originally largely limited to bringing in small numbers of workers to sugarcane farms in Florida and apple orchards in New York, but it has grown tremendously, especially over the past five years.[4] During the 1980s the H-2 visa program split into two different visa types: H-2A and H-2B.[5] H-2A visas employ workers in the agricultural industry, and H-2B visas employ workers in other non-agricultural industries such as seafood processing, forestry, landscaping, and construction.

The program has benefits and drawbacks for both workers and employers. Agricultural employers benefit from access to a skilled workforce when they cannot find enough local workers to fill their open positions, but the financial expenses are high for employers who choose to hire workers through the H-2 visa process. Research has found that pre-employment costs to hire H-2A workers are nearly $2,000 per worker, and the employer must also reimburse the worker for the travel to and from the home country, as well as provide housing for the worker throughout the duration of employment.[5,6] The application process is lengthy and cumbersome for employers.[7] Immigrant workers benefit from access to legal employment in the U.S. and higher wages than they would earn in their home country, but may be exposed to hazardous work conditions and human rights abuses.[1,2,8]

DEMOGRAPHIC DATA & TRENDS

- Approximately 10% of U.S. agricultural workers are employed with H-2A visas.[9]

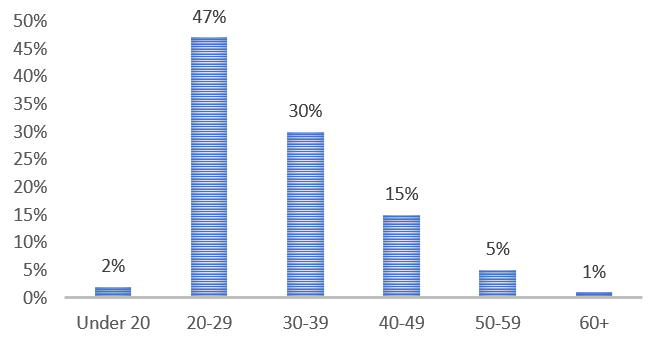

- In the fiscal year of 2018, 97% of nearly 300,000 H-2A workers that were admitted for work in the U.S. were male. Among male workers, the largest proportion (47%) were between the ages of 20 and 29 years (see Figure 1).[10]

Figure 1. Age distribution of male H-2A workers certified for entry in FY 2018

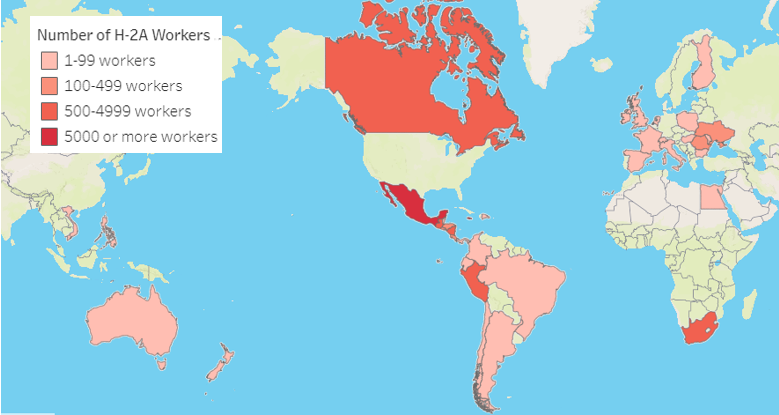

- During the FY 2018, 93% of workers admitted were from Mexico (over 277,000 workers; see Figure 2). More than 5,000 workers (2%) were from Jamaica. Canada, Guatemala, and South Africa each sent 1% of all H-2A workers. Small numbers of workers came from 34 other countries, primarily located in Latin America and Europe.

- The number of H-2A visas issued for workers is lower than the number of H-2A positions certified, since workers may fulfill more than one job with an employer over multiple seasons, or they may transfer later in the season to a different H-2A employer.[9]

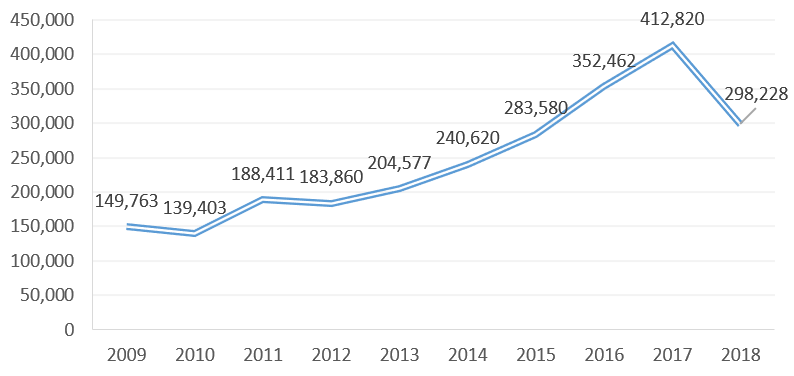

- The increase of the number of H-2A jobs certified has grown steadily each year. The lowest number of immigrants admitted to the U.S. under the H-2A visa since the fiscal year of 2009 occurred in 2010 and the highest occurred in FY 2017. From FY 2010 to FY 2017, the number of immigrants admitted to the U.S. under the H-2A visa program increased by 196%. (see Figure 1).[10]

Figure 3. Number of immigrants admitted to the U.S. under the H-2A visa program, FY 2018.

- Agricultural producers contracted some number of H-2A workers in all 50 U.S. states during FY 2019, but the majority of these workers were concentrated in just five states.[11] North Carolina, Florida, Georgia, California, and Washington had 54% of all certified H-2A positions.

- The majority of H-2A workers are employed in fruits & nuts production and vegetables production.[4]

- The majority (87%) of H-2A positions are paid hourly wages by the employer.[4] The average hourly wage rate has increased, going from $9.30 per hour in 2008 to $12.69 in FY 2019.4,11 After adjusting for inflation, this represents an increase of 14% over the eleven year period.

- A number of academic legal review papers have described a host of issues associated with the H-2A visa program. H-2A workers are excluded from some standard protections, such as the Migrant and Seasonal Worker Protection Act.[12] They also are not able to freely change U.S. employers, so workers may be hesitant to leave an employer or voice concerns about workplace safety or other issues.[13(p)]

- H-2A workers do have some additional rights and protections in comparison to non-H-2A workers. For example, employers are required to provide workers’ compensation coverage for H-2A workers, but this is not required nationally for agricultural workers without H-2A visas.[14]

- Multiple governmental agencies are involved in enforcement of H-2A regulations and screening of H-2A employers, which has been documented to cause confusion among workers and lead to a lack of coordinated enforcement action between agencies.[7] For example, the Department of Labor can debar employers or labor recruiters from participating in the program due to violations of regulations, but limited data sharing with other involved agencies means that ineligible employers can still potentially recruit and hire foreign workers.

- Since workers are recruited outside of the U.S., many employers rely on third-party labor recruiters and recruitment agencies. This system of labor recruiters and a lack of oversight has led to widespread abuse of workers, with labor recruiters charging illegal fees to workers in order to obtain a visa, or recruiters charging other recurring fees or kickbacks when the workers arrive. Recruiters have been reported to threaten workers with blacklisting from future work in the U.S., deportation, or with physical threats to the worker or their family members in the home country.[7,16–18]

- The expenses associated with hiring H-2A workers are substantial. Research has found that employers spend an average of approximately $2,000 per worker just in recruitment and visa application costs.[6] Employers are also required to pay at least the adverse effect wage rate, which is based on the prevailing wage in the local area and is generally higher than the federal minimum wage.19 These expenses may lead some employers to try to recover some of the costs through wage theft, charging fees to workers, or committing other labor rights or health and safety violations.[8,13]

- Research in North Carolina found that H-2A workers experienced wage theft less often than workers without an H-2A visa. Only 4% of H-2A workers reported not being paid wages that were owed them, compared to 45% of workers without H-2A visas.[20]

- Although all H-2A workers should have workers’ compensation coverage under the regulatory requirements of the program, few have health insurance and may have trouble obtaining medical care, especially in very rural and remote areas.[21]

- Research conducted in North Carolina found that 31% of H-2A workers had experienced signs and symptoms of heat-related illnesses at some point during their career in U.S. agriculture.[22]

- In a study examining perceived job safety climates in agriculture, H-2A workers reported similar work safety climates to non H-2A workers, and that they faced similar work hazards.[23]

- Among a sample of Georgia agricultural workers, researchers found that having a H-2A visa was protective against food insecurity.[24]

- Unsanitary and crowded housing has been reported as an issue for some H-2A workers, despite minimum standards for housing from the Department of Labor. All H-2A housing is inspected by governmental agencies, but researchers found numerous violations in inspected housing.[25] Although violations occur, some protection may be provided by the extra oversight from the H-2A program, as research in North Carolina found that H-2A labor camps had fewer housing regulation violations than non H-2A farm labor housing.[26]

- The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has had a disproportionate burden on H-2A guest workers. Numerous media reports have documented outbreaks among H-2A workers across the country, who usually share housing and transportation with dozens or even hundreds of other workers and face multiple barriers to accessing health care services.[27,28] H-2A guest workers have been especially vulnerable since they may lack personal transportation or knowledge of the U.S. health care system, so guest workers are more dependent on the guidance and action of their employer in gaining access to testing, appropriate quarantine procedures, and medical care as compared to domestic workers.

- Nisbet E. Policy and Low-Wage Labor Supply: A Case Study of Policy and Farm Labor Markets in New York State. Washington: Employment and Training Administration, U.S. Department of Labor. Published online 2011. https://wdr.doleta.gov/research/FullText_Documents/ETAOP_2011-13.pdf

- Saadati-Soto D. La Historia Se Repite: Parallels between the Bracero Program and the H-2A Visa Process Highlight the Need for a Decolonial Migrant Labor Policy. Social Science Research Network; 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3627782 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3627782

- U.S. Department of Labor. Fact Sheet #26: Section H-2A of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). Accessed August 27, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/26-H2A

- Luckstead J, Devadoss S. The importance of H-2A guest workers in agriculture. Choices. Published online 2019. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.choicesmagazine.org/choices-magazine/theme-articles/the-role-of-guest-workers-in-us-agriculture/the-importance-of-h-2a-guest-workers-in-agriculture

- Berdikul Qushim ZG. The H-2A Program and Immigration Reform in the United States. Published April 26, 2018. Accessed August 27, 2020. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fe1029

- Roka F M, Simnitt S, Farnsworth D. Pre-employment costs associated with H-2A agricultural workers and the effects of the ‘60-minute rule.’ International Food and Agribusiness Management Review. doi:10.22004/ag.econ.264228 https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Pre-employment-costs-associated-with-H-2-A-workers-Roka-Simnittb/fa4d8dc763e4898233c50d88cd1f91e51339151d

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. H-2A and H-2B Visa Programs: Increased Protections Needed for Foreign Workers [Reissued on May 30, 2017]. 2017;(GAO-15-154). Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-154

- Ripe for Reform: Abuse of Agricultural Workers in the H-2A Visa Program. Centro de los Derechos del Migrante, Inc. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://cdmigrante.org/ripe-for-reform/

- Martin P. Immigration and Farm Labor: From Unauthorized to H-2A for Some? migrationpolicy.org. Published July 31, 2017. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/immigration-and-farm-labor-unauthorized-h-2a-some

- Nonimmigrant Admissions by Selected Classes of Admission and Sex and Age. Department of Homeland Security. Published March 6, 2018. Accessed September 23, 2020. https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/readingroom/NI/NonimmigrantCOAsexage

- Performance Data. Office of Foreign Labor Certification, U.S. Department of Labor. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/foreign-labor/performance

- Ryon C. H-2A Workers Should Not Be Excluded from the Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act. Margins. 2002;2:137. https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=rrgc

- Guerra L. Modern-Day Servitude: A Look at the H-2A Program’s Purposes, Regulations, and Realities. Vt Law Rev. 2004;29:185. https://lawreview.vermontlaw.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/guerra.pdf

- Liebman AK, Wiggins MF, Fraser C, Levin J, Sidebottom J, Arcury TA. Occupational health policy and immigrant workers in the agriculture, forestry, and fishing sector. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(8):975-984. doi:10.1002/ajim.22190 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23606108/

- No Way to Treat a Guest: Why the H-2A Agricultural Visa Program Fails U.S. and Foreign Workers – Farmworker Justice. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.farmworkerjustice.org/resource/no-way-to-treat-a-guest-why-the-h-2a-agricultural-visa-program-fails-u-s-and-foreign-workers/

- Recruitment Revealed: Fundamental Flaws in the H-2 Temporary Worker Program and Recommendations for Change. Centro de los Derechos del Migrante, Inc. Published January 17, 2013. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://cdmigrante.org/recruitment-revealed-fundamental-flaws-in-the-h-2-temporary-worker-program-and-recommendations-for-change/

- Carr EG. Search for a Round Peg: Seeking a Remedy for Recruitment Abuses in the U.S. Guest Worker Program. Columbia J Law Soc Probl. 2009;43:399. http://jlsp.law.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2017/03/43-Carr.pdf

- Clarembaux P, Toral A. Los esclavos de la papa. Univision. Accessed August 26, 2020. https://www.univision.com/especiales/noticias/2020/los-esclavos-de-la-papa/index.html

- Stockdale KE. H-2A Migrant Agricultral Workers: Protected from Employer Exploitation on Paper, Not in Practice. Creighton Law Rev. 2012;46:755. https://dspace2.creighton.edu/xmlui/handle/10504/48347

- Robinson E, Nguyen HT, Isom S, et al. Wages, Wage Violations, and Pesticide Safety Experienced by Migrant Farmworkers in North Carolina. New Solut. 2011;21(2):251-268. doi:10.2190/NS.21.2.h https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/nioshtic-2/20040292.html

- Bail KM, Foster J, Dalmida SG, et al. The Impact of Invisibility on the Health of Migrant Farmworkers in the Southeastern United States: A Case Study from Georgia. Nursing Research and Practice. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/760418 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22830007/

- Mirabelli MC, Quandt SA, Crain R, et al. Symptoms of Heat Illness Among Latino Farm Workers in North Carolina. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(5):468-471. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.07.008 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2963149/

- Arcury TA, Summers P, Talton JW, Nguyen HT, Chen H, Quandt SA. Job Characteristics and Work Safety Climate among North Carolina Farmworkers with H-2A Visas. J Agromedicine. 2015;20(1):64-76. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2014.976732 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25635744/

- Hill BG, Moloney AG, Mize T, Himelick T, Guest JL. Prevalence and Predictors of Food Insecurity in Migrant Farmworkers in Georgia. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(5):831-833. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.199703 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3076419/

- Mora DC, Quandt SA, Chen H, Arcury TA. Associations of Poor Housing with Mental Health Among North Carolina Latino Migrant Farmworkers. J Agromedicine. 2016;21(4):327-334. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2016.1211053 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5019947/

- Arcury TA, Weir M, Chen H, et al. Migrant farmworker housing regulation violations in North Carolina. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55(3):191-204. doi:10.1002/ajim.22011 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3708262/

- Flocks J. The Potential Impact of COVID-19 on H-2A Agricultural Workers. J Agromedicine. 2020;0(0):1-3. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1814922 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32856557/

- MSAWs and COVID-19. NATIONAL CENTER FOR FARMWORKER HEALTH. Accessed July 20, 2020. http://www.ncfh.org/msaws-and-covid-19.html

This publication was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $1,916,466 with 0% financed with nongovernmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.