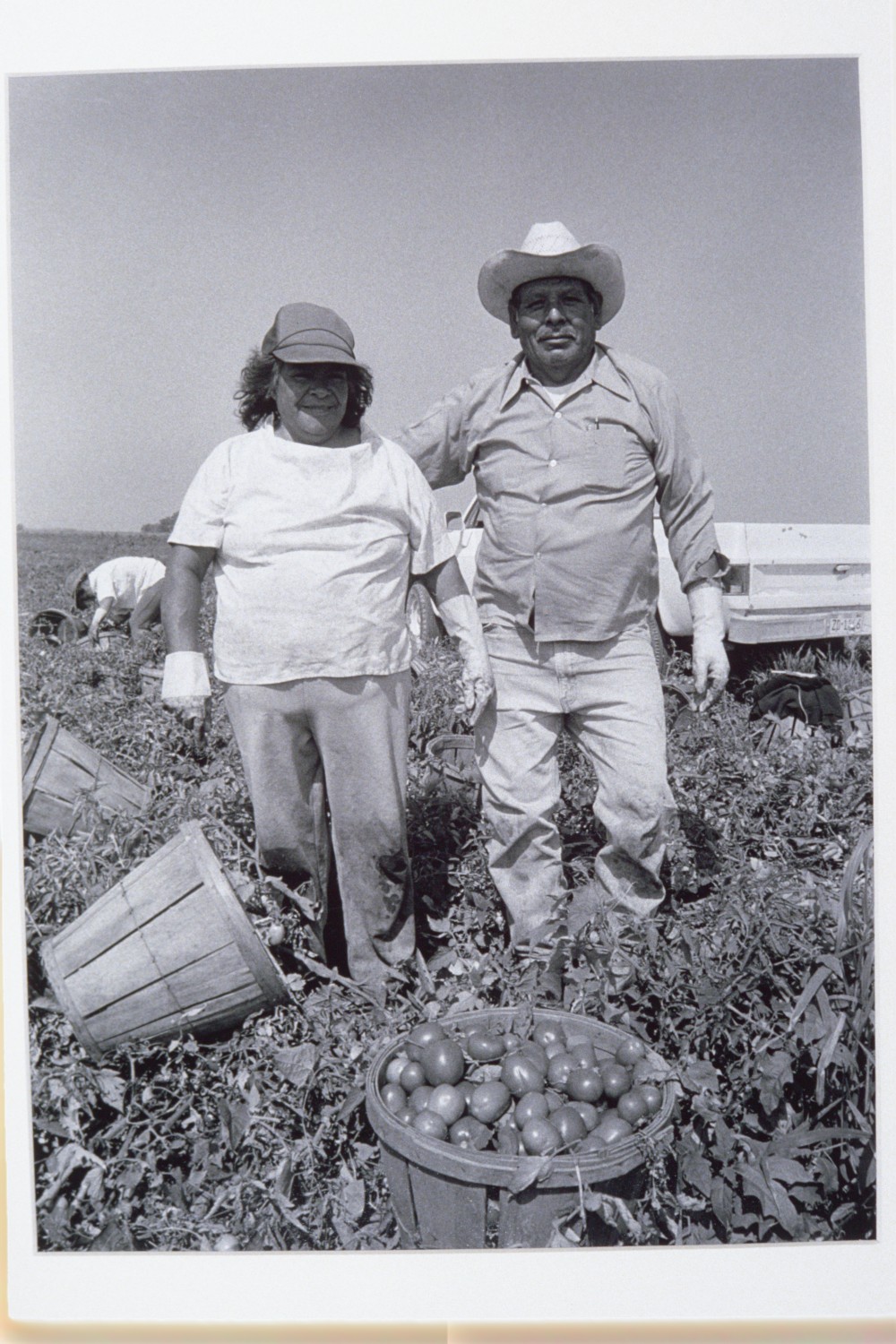

“The hands that feed us are often invisible hands, hands of people who work in the shadows of a multibillion-dollar industry without enjoying its rewards.”

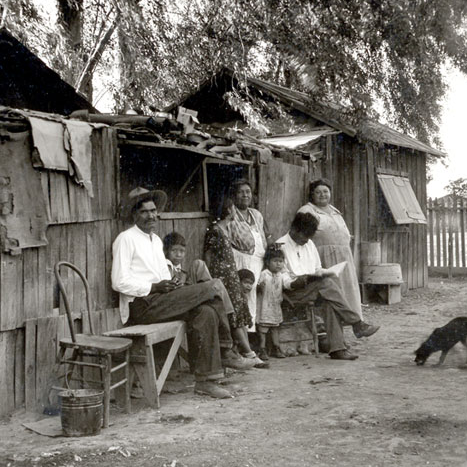

The history of migrant and seasonal farmworkers is almost as old as the country itself. Farmworkers have always lived in the shadows of communities, living and working under hazardous unsanitary conditions while surviving on meager wages with poor access to education, welfare, and health care. From our nation’s creation, agriculture and the small family farmer were considered essential components of democracy. These small farmers, except in the slave dependent South, relied on family, locally hired hands, or neighbors to meet the seasonal labor demands of agriculture.

As the crop production grew larger and more specialized, labor was required on a more seasonal basis. By the 1850s, demand for farming production increased to a level that immigrants from several countries were brought in by employment agencies to meet the demand. Along the east coast, African Americans and poor Anglos joined newly arriving European immigrants as part of the seasonal labor force. While on the west coast, farmers began hiring large numbers of immigrants from China, Japan, and Mexico. In the South, the seasonal need was met by slaves, and after the Civil War, by former slaves, Native Americans, and poor Anglos.

The growing demand for seasonal labor was a process that continued through the rest of the 20th century in America. As farming production grew larger and larger, smaller farms that were once the economic backbone for rural communities were absorbed. Small rural communities died out, migration from rural to urban areas increased, and the labor supply needed for these large and specialized farming productions was no longer locally available.

In addition, the need for seasonal labor was aided by the introduction of new machinery, farming methods, and herbicides. These advances increased the cost of farming, which necessitated even larger productions, which, in turn, led to an increased dependence on seasonal and manual labor. Advancements in transportation exacerbated the situation. Better roads and refrigeration in transportation allowed farming productions to operate in even greater isolation from domestic labor supplies, which led to the increased demand for a temporary and migratory seasonal labor force.

By 1900, U.S. cities grew and our industrial base expanded to a point where large-scale commercial agriculture became an economic necessity, and with it a labor force tailored to its needs.

The demand for immigrant labor continued into 1917, when the U.S. entered into World War I (WWI). As a result of the war, the country was faced with growing war time food demands and an increased shortage of agricultural laborers. In response, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1917. This law established a legal basis for the importation of some 73,000 Mexican workers.

In the 1920s, as WWI came to an end, agriculture continued production at wartime levels. However, absent the wartime demand, crop prices plummeted and the need for cheap labor intensified. In the meantime, supplies of domestic agricultural labor in the South dropped as African American and White sharecroppers began to migrate elsewhere. Mexican laborers were highly desirable, and immigration from Mexico increased.

Like all other industries in the United States at the time, the agricultural economy worsened with the onset of the Great Depression. Foreign demand for U.S. agricultural exports plummeted and prices dropped. In an effort to open up jobs to native-born citizens, the Immigration and Naturalization Service cooperated with local authorities to deport Mexican immigrants and Mexican-American citizens by the thousands. In all, more than 400,000 “repatriados” were deported.

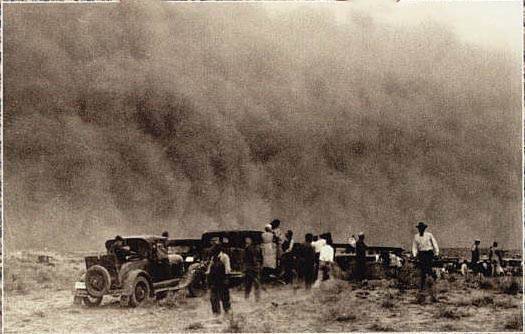

Domestic agricultural workers were initially reluctant to fill the migratory labor positions; however, they were left with little choice following droughts in the mid 1930s. Over-farming and poor soil management, combined with the drought conditions, created vast dust storms that devastated the lower Great Plains. Farmers in these areas were soon displaced, giving way to the tough economy, dusty conditions, and land foreclosures. They became the new migrants, traveling to California and other regions in search of work and substance.

The United States entered World War II on December 8, 1941. To meet the challenge of war, industrial and agricultural production increased and much of the nation’s human resources were diverted to the military. Similar to their experiences in World War I, commercial farmers faced a high demand for their products, but growers were without sufficient labor to produce them.

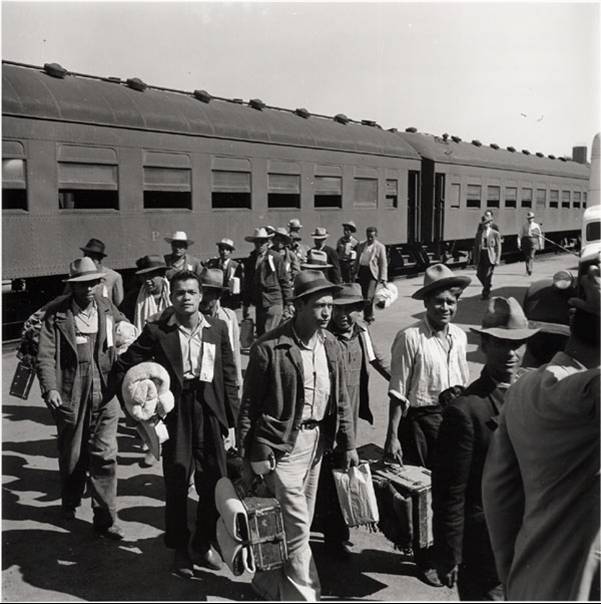

The United States once again called upon Mexico to fill the labor void. The two countries signed the Bracero Agreement in 1943, which began the importation of laborers or “braceros” from Mexico to work in the United States.

Although originally devised to meet World War II shortages, the Bracero Program continued until 1964 under a variety of legislative authorities, ultimately employing 5 million Mexican laborers. Following the termination of the Bracero Program in 1964, farm employers turned to the H-2 program for their labor needs. This program, now known as the H-2A program, continues today.

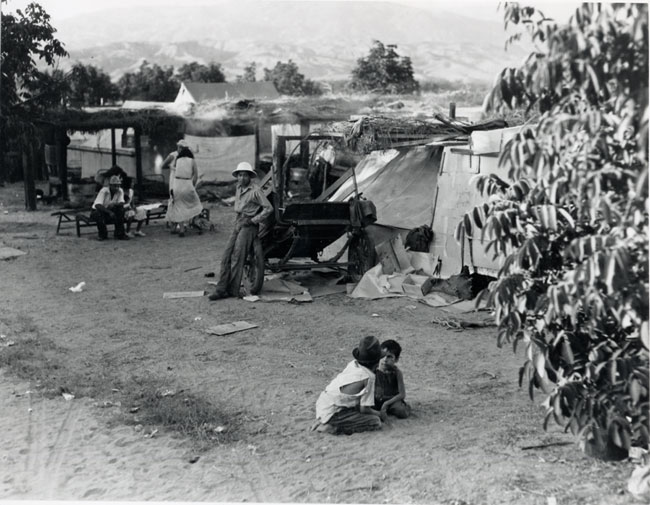

As the initial phase of the Bracero Program ended in the early 1950s and the number of migrant workers grew larger and larger, two Presidential Committees were established to investigate various aspects of domestic and foreign migratory labor. The committees’ research revealed poor social, economic, health, and educational conditions of farmworkers of the day.

While the President’s Committees were indicative of an increased interest in migrant welfare, so were the activities of the Public Health Service (PHS). Traditionally, the Public Health Service provided services and preventative care on a community basis. In the early 1950s, the Public Health Service began to expand its migrant-specific services. This trend would eventually result in the creation of the Migrant Health Unit, the precursor to today’s Migrant Health Program.

Public awareness of migrant farmworkers and the conditions they lived in surged during the 1960s. One of the first steps in increasing public awareness for farmworkers was the Edward R. Murrow documentary titled “Harvest of Shame”, which aired on Thanksgiving Day, 1960. The program detailed the exploitation of migrant farmworkers by large agribusiness and highlighted their poor living and working conditions. In addition to the documentary, the farm labor movement of the 1960s had a great impact on the public and the lives of farmworkers.

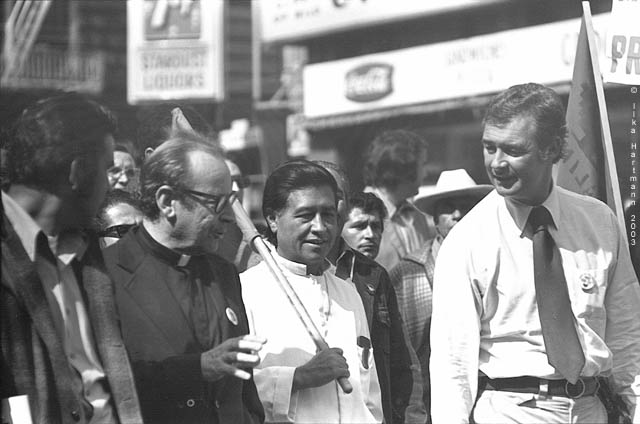

Two organizations, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) and the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), led a series of successful strikes against growers in California. Under the leadership of Cesar Chavez, the organizations asked for union recognition and to be paid a living wage. Eventually, the growers submitted, and the unions received official recognition from the largest growers in the area. Chavez became the public face of farmworkers, and he and his movement gained national attention and were spotlighted by various media outlets.

As a result of the growing farmworker awareness, a Senate Sub-Committee on Migratory Labor began working on a comprehensive bill to address a variety of migrant labor concerns. The bill emphasized the need for a simple and flexible program, adapted to the needs of migrant workers, and focused on the provision of health services. It was written so that the Public Health Service would be given authority to make grants available to health projects serving the domestic migrant population. The bill passed both houses of Congress and was signed into law by President John F. Kennedy in September of 1962 as the Migrant Health Act.

Shortly after the bill’s passage, the Migrant Health Unit became the Migrant Health Branch, and was charged with administering the new program. The program was designed to allocate funds, facilitate inter-agency cooperation, disseminate information, and monitor the health status of migrant farmworkers. The Migrant Health Program was reauthorized in 1963 and again in 1966, adding hospitalization to the scope of services provided by migrant clinics. By 1969, 118 projects were in operation, serving 317 counties in 36 states and Puerto Rico.

In the 1970s, reauthorization of the Migrant Health Act created the National Advisory Council on Migrant Health. The Council, which still exists today, is legislatively mandated to advise, consult with, and make recommendations to the Secretary of Health and Human Services on the health and well-being of migrant farmworkers and their families. Fifteen members are appointed by the Secretary to serve four-year terms.

Also, in 1970, Congress added the phrase “other seasonal farmworkers” to the eligible recipients of migrant health grant-assisted services. This was done to include seasonal farmworkers who were often indistinguishable from migrant farmworkers in the major home base areas where migrants reside throughout the country. This wording increased the target population of the migrant health program from an estimated three-quarter million migrants and family members to 2.75 million.

The bill reauthorizes and consolidates four Federal health primary care and prevention programs: community health centers, migrant health centers, health care for the homeless, and health care for residents of public housing programs. By empowering communities to design and develop their own local solutions to their health care access problems, this legislation will help to improve the health status of our Nation’s medically underserved, low-income populations. The Nation’s health centers, comprised of over 700 organizations and 2,100 service delivery sites.

As the1980s began, the migrant health program entered its third decade. Two major legislative acts were also passed in the 1980s. First, in 1983, The Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Workers Protection Act passed. This act requires farm labor contractors, agricultural employers, agricultural associations, and providers of migrant housing by forcing them to meet certain minimum requirements in their dealings with migrant and seasonal agricultural workers.

The second act passed in the 1980s was the Immigration Reform and Control Act in 1986. This act instituted penalties against employers that knowingly employed illegal workers. It also created the Special Agricultural Worker program, which allowed illegal farmworkers legal immigrant status if they had worked at least “90 man-days” between May 1985 and May 1986.

The Health Centers Consolidation Act of 1996 was one of the most important acts passed in the last 30 years regarding migrant health. This act brings together under one grant structure Community Health Centers, Migrant/Seasonal Farmworker Health Centers, Health Care for the Homeless Health Centers and Health Centers for Residents of Public Housing.

In recent years, the migrant health branch was incorporated into the Office of Minority Health within the Health Resources and Services Administration. However, the health centers supported by the Bureau of Primary Health Care’s Consolidated Health Centers Program continue to meet the challenge by providing health care to migrant and seasonal farmworkers throughout the United States. With over 154 migrant health centers operating in 42 states, and serving more than 807,000 MSFW patients in 2006, the migrant health program has come a long way since it began as small health units more than 70 years ago.