|

A woman is a very central, matriarchal, and necessary part of the traditional Hispanic household. Oftentimes one thinks of migrant workers as young men coming to the country to work in the fields. The women who accompany them are too often seen as passive passengers on the dangerous journey many migrant workers face each season.

The month of March honors Women’s History Month. It is important to take time and show recognition for the strong women in the fields who are much more than a passive voice accompanying their male counterparts. “There is no question,” great civil rights and farmworker activist Dolores Huerta says, “that our women are strong. They work right alongside the men in the fields.” And when the day’s labor is done the women go home, cook for their families, help their children with homework or if they’re younger, bathe and feed them. It is very rare that the female farmworker takes time for herself, and she rarely asks for it. There is too much work to be done. Ms. Huerta is right, there is no question whether America’s farmworking women are strong. The question is; how do we give this silent population a voice? According to Cultural Survival there is little known information on the health status of migrating women in the United States. Undocumented female workers face unique barriers, among them, poor occupational health and safety, poor diet, and most are unfamiliar with the affordable health services they are eligible for. The barriers mentioned above do not exclusively affect women. However, one fear that women have reported more frequently than migrant men is the fear of sexual abuse. Many migrant women do not report cases of sexual assault because they fear repercussions. Nearly 50% of the migrant agricultural workforce are undocumented immigrants; too often women remain silent because of their fear of termination or deportation. In the rare occasion that a woman reports abuse, it is usually lengthy process that is not sustainable or affordable for a low-income migrating family. It goes without saying that sexual abuse can cause physical and emotional harm to our women in the fields, especially when abusers are not charged for their crimes. So what can we do to help our mothers, sisters, and daughters in the fields? Community Health Workers and Promotoras de Salud can go out in the fields and educate both men and women on what constitutes as sexual abuse. There are some laws that protect our female farmworkers as well. Abuse in the fields is unacceptable. Abuse in the fields without knowing how to access health services is unacceptable. The National Center for Farmworker Health is calling on Migrant and Community Health Centers to increase their number of farmworkers served to 2 million by the year 2020. No one should fear their mortality or safety because of lack of access to primary and preventative health care services. Find out other ways you can get involved to help women in the fields raise their voices. Photo Credit: iStock It is Christmas season and we see Christmas trees everywhere. Christmas trees are put up each year, yet many don’t stop to reflect on the hard work and consequences that agricultural workers experience in order for these trees to be in our homes. Prior to the 1950's, most Christmas trees were cut from the forest. Today, according to the National Christmas Tree Association, more than 90 percent are grown on farms growing nearly 350 million Christmas trees in the U.S. alone. There approximately 15,000 farms growing Christmas Trees in the U.S. and employing over 100,000 people full or part-time in the industry. With the high demand for Christmas trees during this season, agriculture workers working the pine trees become essential for the industry. However, they are exposed to the dangers of pesticides, herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, along with other occupational health risks. When we see Christmas trees during this season, it’s uncommon to stop and think of the dangers farmworkers face while working. Yet, more shocking is the fact that many of them have not received any health care services. For example, North Carolina is the leading producer of Fraser fir trees, one of the best selling Christmas tree species, but in 2014, in North Carolina only 10.5% of agriculture workers received health care services. Due to a low percentage of agricultural workers in the U.S being served by health centers, NCFH and NACHC have launched the Ag Worker Access 2020 campaign calling on every migrant health center grantee to increase the number of agricultural workers served by 15% each year over the next five years. NCFH has developed resources and tools to help health centers achieve this goal. Every agricultural worker deserves to be aware of his or her health care opportunities, accounted for in their health center, and receive quality health care services. They work the soil of this country for all of us to have food on our tables, and even to make our home look beautiful with a Christmas tree during the holiday season. So, join us in making this Ag Worker Access 2020 campaign a success and most importantly making sure all agricultural workers and their families receives health care services. In this holiday season, learn how you can help ensure agricultural workers are informed of the health care services available to them. And remember, if you have a beautiful decorated Christmas tree in your home…thank a farmworker. By: Joanna Arevalo

Video: Robyn Levine, USA, 2011.  Perhaps unlike many, my connection to the American agricultural production system exists through living relatives. In a sleepy small town in Tennessee, my grandparents still reside in a one-story, ranch-style house amidst miles of farmland, although they no longer work their land themselves or manage the harvesting of crops - and haven’t since retiring. As a child, I remember running through tall cornstalks chasing my sisters and avoiding bees. I remember small bean plants and rides on my grandpa’s John Deer tractor. I remember long discussions of the poor planting decisions of neighbors and dismay at the piece-by-piece selling of land in the area for economic survival. Even with these fond memories and close encounters with our nation’s changing food production system, I still consider my understanding of the lives of migrant and seasonal ag workers relatively infantile. Fortunately, I found my premier attendance at NCFH’s Annual Midwest Stream Forum served as a giant gateway to increasing that understanding. From explanatory sessions on how U.S. social programming addresses the unique needs of ag workers to fervent discussions of how to champion increased access to health care for this population, I found myself in a diverse community of advocates, researchers, public health leaders and front-line health service delivery workers. We were all curious to hear each other’s stories and perspectives, anxious to build on our tools for meeting the needs of those who keep America fed. This year’s Keynote Speaker, Judge Juan Antonio Chavira, provided attendees with valuable insight into the importance of accommodating, respecting and recognizing the influence of curanderismo, Mexican American folk healing, when treating some agricultural worker patients. He said our prerogative as champions of ag worker health should not be to convince someone that their way of healing is incorrect but that both fields of thought might work together to meet patients’ needs. Instead of being right, “the idea is to make people well,” he said. On behalf of NCFH, thank you so much to everyone that attended and supported this year’s event in Albuquerque. On behalf of myself, a fellow learner and growing champion, may the lessons and conversations from the forum continue to inspire us to better serve agricultural workers in innovative, respectful and culturally appropriate ways. By Lindsey Bachman Photos: Lindsey Bachman A few notable resources highlighted at this year's forum:

Join the ongoing conversation regarding increased access to quality health care for agricultural workers. Follow #MWSF2015 and #AGACCESS2020 on Twitter (@NCFHTX), Facebook and Instagram (@farmworkerhealth). This year's Midwest Stream Forum was about growing champions of migrant health. Tell us about how you champion migrant health by leaving a comment below.

It is Health Literacy Month.

It’s alarming to think that only 12% of American adults are considered health literate, according to the National Assessment of Adult Illiteracy. In other words, nine out of ten Americans lack the basic knowledge to manage their health and prevent disease. This holds true for the vulnerable populations of our country, including migratory and seasonal agricultural workers. These populations face barriers to a basic understanding of their health and to receiving appropriate health education. Health Literacy – put simply – is one’s ability to understand and obtain health information. That is the simple definition. A much more complex definition resides in the specific factors and barriers contributing to a population’s lack of health literacy, which can correlate (not exclusively) to a person’s language, culture, location, and socioeconomic environment. Migratory and seasonal agricultural workers face unique obstacles to managing their own health care, including access to transportation to services, language barriers, and (in some cases) not being treated well due to undocumented status. When blockades exist to access to health, one’s access to health education will also be barricaded. Migrant and Community Health Centers strive for the elimination of health illiteracy among all their patients by providing preventive treatment and low literacy education materials for patients to learn more about a specific diagnosis or their risk factor(s). The patient is not solely responsible for his or her healthcare and health education. Health center staff are being trained to become culturally competent in their respective positions. Cultural competency – according to Health.gov – “is the ability of health organizations and practitioners to recognize the cultural beliefs, values, attitudes, traditions, language preferences, and health practices of diverse populations, and to apply that knowledge to produce a positive health outcome. Competency includes communicating in a manner that is linguistically and culturally appropriate.” NCFH prides itself on our ability to orient and train staff to implement cultural competency curriculums in the migrant and community health centers we serve. Participants of NCFH cultural competency courses learn to understand the meaning of diversity and its relationship and impact on communication and human relations. Along with that they increase awareness of their personal attitudes, beliefs and behaviors related to cultural diversity; and enhance skills for improved cross-cultural communication. NCFH also offers low literacy and English/Spanish translation services in order to continue improving a patient’s health literacy. Improving a health center staff’s cultural competence and patients' overall health literacy, allows for more involvement with, and awareness of, the diverse populations that health centers serve, and ultimately contributes toward eliminating one of the many barriers a patient faces related to health literacy. By: Mindy Morgan Behavioral and mental illness disorders remain part of a large conversation among the American public, and recent events make the need for depression and other mental health disorder screenings a must for health centers that serve the vulnerable communities in our country. Community Health Centers (CHCs) realize the very real concern of behavioral health issues among these populations. Nearly 70% of CHCs are screening for depression and other related mental health disorders around the nation, while 40% provide substance abuse counseling and treatment. According to the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC), “Persons living with mental illness have a higher mortality rate and often die prematurely due to preventable diseases such as: diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases, and infectious diseases.” The good news? There has been a dramatic growth in assessing the quality measures of behavioral health within the last decade. Although there is a growth in assessment, there is still work to be done. U.S. migrant and agricultural workers suffer with a higher susceptibility to the risks of behavioral health and its diagnosis. Migrant agricultural workers who are separated from their families may be more susceptible to mental health disorders, such as depression, alcoholism, and substance abuse. Nervios is a “culturally defined definition of stress.” A study conducted by National Agricultural Worker Survey (NAWS) reported that 20% of male agricultural workers experienced some form of Nervios and those who were separated from their families had reported a higher rate at 28%. When behavioral and mental health goes untreated, the results can be devastating on a personal and communal level. Many untreated disorders result in patient suicides, incarceration, homelessness and severe episodes of violence. To find a Community Health Center offering depression screening please visit: http://findahealthcenter.hrsa.gov/ By Mindy Morgan

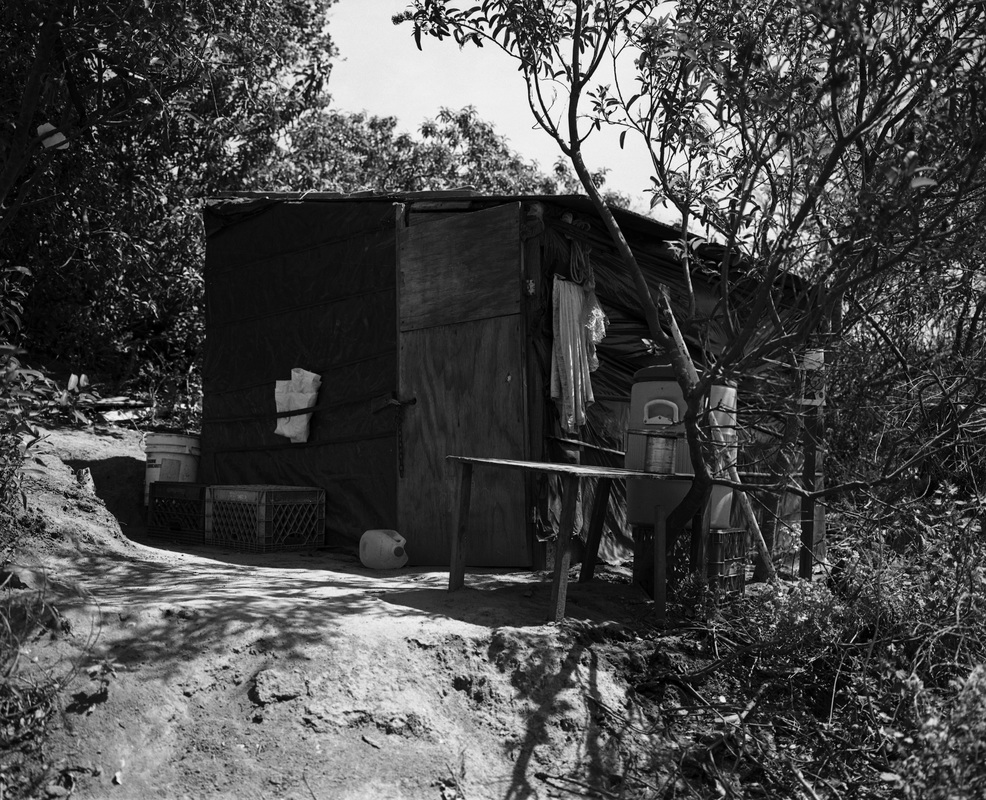

Photo: Alan Pogue Although there has been substantial progress in cancer treatment, screening, diagnosis, and prevention over the past several decades, addressing cancer health disparities—such as higher cancer death rates, less frequent use of proven screening tests, and higher rates of advanced cancer diagnoses—in certain populations is an area in which progress has not kept pace. These disparities are frequently seen in people from low-socioeconomic groups, certain racial/ethnic populations, and those who live in geographically isolated areas. – National Cancer Institute  The U.S. Latina population has lower-rates of breast cancer than non-Hispanic women. However, they have a 20% greater chance of dying than other women after receiving a positive diagnosis. Many attribute this discrepancy to the social determinants of health that influence patient survival – including a lack of access to quality education and healthcare, which is exacerbated by patients’ socioeconomic statuses. The unique seasonal and migratory lifestyles of female agricultural workers further compound and complicate these issues – as do the effects of existing misinformation regarding screenings and cultural beliefs amongst this population. The necessity of consistent appointments and follow-ups for effective care proves problematic for those on the move and those working under severe occupational time constraints. Women over the age of 50 are urged to get annual mammograms in addition to performing frequent self-examinations. However, a positive exam only constitutes an initial step in the breast cancer diagnosis process. Patients must return and provide a tissue sample before the disease is confirmed. Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) served more than 2 million women over the age of 50 and 440,000 women utilized services at Migrant Health Centers in 2014. FQHCs also performed more than 470,000 mammograms and found almost 110,000 breast abnormalities last year. The National Center for Farmworker Health recognizes the need for a special focus on breast cancer outreach to the U.S. female agricultural worker. Through its Cultivando la Salud program, NCFH offers health centers and other Hispanic-serving organizations the opportunity to receive train-the-trainer instruction intended to provide program planners with the knowledge, step-by-step process, and the tools to successfully plan and develop a comprehensive breast and cervical cancer education program for the agricultural population as well as other Hispanic communities. The training includes basic program planning information from designing the program goals and objectives to developing a budget to recruitment and training of lay health workers. The program also includes an evaluative component and specialized focus on the teaching tools lay health workers will be using in the community. At the end of the training, training participants will be provided with a complete training curriculum, a program manual to guide the implementation of the program, and the CLS teaching tools for lay health workers to use in the community. By Lindsey Bachman

Photo: Steve Debenport, iStock On Monday, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced a series of revisions to its existing pesticide regulations in hopes of providing additional protection to agricultural workers in the United States. Approximately 16% of the 2.4 million agricultural workers represented in the 2012 National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) reported loading, mixing or applying pesticides in the last 12 months. That’s almost 400,000 workers. The effects of ag worker pesticide exposure reportedly generate $10-$15 million in healthcare costs each year. In the Huffington Post on Monday, Gina McCarthy, U.S. EPA Administrator, and Thomas E. Perez, U.S. Secretary of Labor, wrote: There are serious financial consequences for businesses that don't acknowledge the importance of worker safety. They not only endanger their own workers, they reduce their competitiveness and harm their bottom line. It's time to raise the bar for our agriculture workers in the United States. The article also included insight from Norma Flores, a woman from a migrant ag worker family, who now works for the East Coast Migrant Health Project. Migrant farm labor supports the approximately $28 billion fruit and vegetable industry in the United States. At NCFH, we proactively support the work of migrant health centers and the empowerment of farmworker communities in our mission to improve health status. We are determined to eliminate the barriers to health care and increase access for farmworker families to culturally appropriate quality health care. By Lindsey Bachman

Photo: iStock |

The National Center for Farmworker HealthImproving health care access for one of America's most vulnerable populations Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed