|

During Thanksgiving we take time to reflect on all that we are grateful for. As always, but especially during Thanksgiving, we take time to remember those who work tirelessly to bring fresh, affordable produce to our tables for our family meals every day – Agricultural Workers and the farmers that employ them.

For the past 40 years, NCFH has worked to improve the health status of Agricultural Workers and their families by providing population-specific information, training, and technical assistance to the health centers, organizations and other individuals who serve them. This year we, along with the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC), launched the Ag Worker Access 2020 Campaign, with the goal to increase the number of Agricultural Workers with access to comprehensive and high quality services at community health centers to 2 million by 2020. As NCFH celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, we’d like to take this opportunity to express our gratitude to all of you who have helped, and continue to help, NCFH achieve its mission – health centers, primary care associations, our Board of Directors, staff, and other partners, to name only a few. You have shared your skills, knowledge, and especially your heart toward our common goal, and we are humbled and truly grateful. We at NCFH wish you, our migrant health champions, a safe and happy Thanksgiving. As we look forward to our organization’s next milestone in 5 years we will not only be celebrating NCFH’s 45th anniversary, but also the success of the Ag Worker Access 2020 Campaign. What a celebration that will be! By: Lisa Miller Photo: NCFH

Dear Migrant Health Champion,

This year, on Tuesday, December 1, 2015, the National Center for Farmworker Health is participating in #GivingTuesday, a global day dedicated to giving. We ask that you help support us in this endeavor. In additional to promoting migrant health awareness, we will request that our community support migrant health scholarships through our online store or make a donation to our Call for Health Program. All proceeds from this initiative will support the Migrant Health Scholarship Program and the Call for Health Foundation. About NCFH’s Migrant Health Scholarship Award and Call for Health Program Each year NCFH accepts applications for the Migrant Health Scholarship Award from individuals employed or interning at federally funded migrant health centers. Applicants are staff members who desire to further their education and are either currently studying or entering a curriculum relevant to migrant health. The selection committee reviews applications based on the following criteria: applicability of educational goals to migrant health, personal statement of experience or commitment to migrant health, letters of reference, farmworker status, and length of service in the migrant health field.

Call for Health is a national patient navigation system that promotes health and well-being for farmworker families through bilingual educational publications and is a national call line that responds to questions on accessing local health care resources for farmworkers. The Call for Health Foundation provides financial assistance to help farmworker families access healthcare services.

The national toll-free number (800-377-9968) is staffed by bilingual Information Specialists Monday through Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Central Time, and is accessible 24 hours a day through voice messaging. About #GivingTuesday Last year, more than 30,000 organizations in 68 countries came together to celebrate #GivingTuesday. Since its founding in 2012, #GivingTuesday has inspired giving around the world, resulting in greater donations, volunteer hours, and activities that bring about real change in communities. We invite you to join the movement and to help get out the give this December 1. 5 Ways to Support NCFH’s Participation in #GivingTuesday

Thank you. One in every ten Hispanic/Latino persons will develop Diabetes Type 2 after the age of 20, according to the National Diabetes Education Program. Of those 10%, nearly 12% are of Mexican ethnicity. The ethnically Mexican population, both documented and undocumented, accounts for 68% of the Agricultural Worker population in the United States.

Naturally, with Diabetes risk factors being higher within Latino populations, it is important for special vulnerable populations – like the United States’ Migrant Agricultural Workers – to have provided to them the important tools and resources for both understanding the risk of Diabetes and how to manage it if diagnosed. Diabetes Type 2 (or Diabetes Mellitus) happens when our bodies cannot process glucose (or sugar) like it used to. Sugar levels rise and our bodies try to make up for it by producing more insulin. However, after time the body cannot regulate the process and thus Diabetes Type 2 is diagnosed. Symptoms of Diabetes Type 2 often include feeling fatigued, thirsty, numbness in the feet and hands, blurred vision, and higher susceptibility to cuts and bruises that won’t heal. Agricultural Workers face a greater risk due to their specific barriers to health care. Lack of health insurance and transportation are big factors. But Dr. Keshelava also reported that workers might fear the retaliation of their superiors if they are feeling sick. Retaliation can be hours cut or being fired. The good news is there are ways to manage Diabetes Type 2 within the migrant Agricultural Worker population. A collaborative Farmworker Health Network member, MHP Salud, has programs that train Community Health Workers to go out in the fields and offer culturally appropriate education on Diabetes Type 2. NCFH, in coordination with Consumer Reports Best Buy Drugs, has created low-literacy and culturally appropriate factsheets for Migrant Health Centers to provide patients who have been diagnosed with Diabetes Type 2. Written By: Mindy Morgan Photo: iStock There are many efforts that endeavor to illuminate the diversity of our country. It could be argued, however, that none reach further or strike the cords of humanity deeper than personal storytelling. The National Center for Farmworker Health proactively supports the work of migrant health centers and the empowerment of Agriculture Worker communities in our mission to improve health status. We remain determined to eliminate the barriers to health care and increase access for Ag Worker families to culturally appropriate, quality health care. In light of this resolve, we work actively to promote awareness regarding the American ag worker’s contribution to United States’ food production as a whole. Not all ag workers are undocumented, but many are immigrants. Many are third and fourth generation Americans. As a country comprised historically of immigrants, we think it is important to share with our community the story of one organization working to tell the stories of our country’s populations: Define American. Since its inception in 2011, Define American has been working to start and facilitate conversations regarding immigration in the United States. Part of this effort has included a series of personal vignettes, including the one below from Jose Antonio Vargas, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and the organization’s founder and co-chair. He says, “I define American as someone who works really hard,someone who is proud to be in this country and wants to contribute to it. I am independent. I pay taxes. I’m self-sufficient. I am an American.” If you have a story to tell, or want to recommend someone whose personal family journey will lend meaning to the definition of “American”, we encourage you to share also. As a first generation American, produced from two generations of orphans, I am extremely conscious of the blessings and good fortune that have marked my life and that of my children. I’ll tell my story. Look for it on Define American. Will you tell yours?

By Bobbi Ryder, NCFH President and CEO Photo: Lindsey Bachman  Perhaps unlike many, my connection to the American agricultural production system exists through living relatives. In a sleepy small town in Tennessee, my grandparents still reside in a one-story, ranch-style house amidst miles of farmland, although they no longer work their land themselves or manage the harvesting of crops - and haven’t since retiring. As a child, I remember running through tall cornstalks chasing my sisters and avoiding bees. I remember small bean plants and rides on my grandpa’s John Deer tractor. I remember long discussions of the poor planting decisions of neighbors and dismay at the piece-by-piece selling of land in the area for economic survival. Even with these fond memories and close encounters with our nation’s changing food production system, I still consider my understanding of the lives of migrant and seasonal ag workers relatively infantile. Fortunately, I found my premier attendance at NCFH’s Annual Midwest Stream Forum served as a giant gateway to increasing that understanding. From explanatory sessions on how U.S. social programming addresses the unique needs of ag workers to fervent discussions of how to champion increased access to health care for this population, I found myself in a diverse community of advocates, researchers, public health leaders and front-line health service delivery workers. We were all curious to hear each other’s stories and perspectives, anxious to build on our tools for meeting the needs of those who keep America fed. This year’s Keynote Speaker, Judge Juan Antonio Chavira, provided attendees with valuable insight into the importance of accommodating, respecting and recognizing the influence of curanderismo, Mexican American folk healing, when treating some agricultural worker patients. He said our prerogative as champions of ag worker health should not be to convince someone that their way of healing is incorrect but that both fields of thought might work together to meet patients’ needs. Instead of being right, “the idea is to make people well,” he said. On behalf of NCFH, thank you so much to everyone that attended and supported this year’s event in Albuquerque. On behalf of myself, a fellow learner and growing champion, may the lessons and conversations from the forum continue to inspire us to better serve agricultural workers in innovative, respectful and culturally appropriate ways. By Lindsey Bachman Photos: Lindsey Bachman A few notable resources highlighted at this year's forum:

Join the ongoing conversation regarding increased access to quality health care for agricultural workers. Follow #MWSF2015 and #AGACCESS2020 on Twitter (@NCFHTX), Facebook and Instagram (@farmworkerhealth). This year's Midwest Stream Forum was about growing champions of migrant health. Tell us about how you champion migrant health by leaving a comment below.

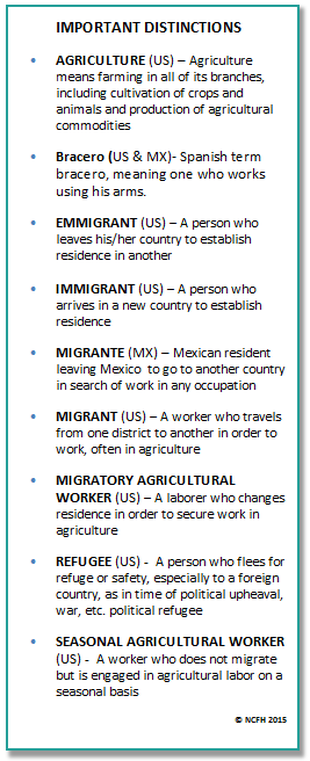

Next week, members of the NCFH team will gather in Albuquerque, New Mexico for the 25th Annual Midwest Stream Forum. In light of recent global events, the importance of terminology in our work remains a persistent and important subject that merits intentional discussion and reflection. The content below constitutes an extended version of NCFH CEO Bobbi Ryder’s remarks in the Forum’s welcome letter.

These few days represent a unique opportunity for us to come together, share experiences, and explore new ideas in hopes of influencing the Migrant Health Movement’s progress toward increasing access to quality care for agricultural workers in the United States.

In light of our gathering and some tragic global events of late, many specific details related to our work seem more compelling to me now more than ever. For many decades the use of the word migrante by our colleagues in Mexico was thought by many to mean the same as its cognate, migrant in the English language, thus leading to confusion between immigrants, documented or undocumented, and domestic migratory agricultural workers. Because of such word associations the term migrant has come to connote a stigma and reduces the stature of this vital workforce. Recent publicity about the plight of those fleeing Syria to Europe and the U.S. caught my attention with of the interchangeable use of the terms migrant and refugee. European opposition to the arrival of these refugees evokes images of a largely unwanted and abused population with little sympathy for the terror that they seek refuge from. Calling them migrants both diminishes the reality of the political strife in Syria, adds confusion to popular understanding of the term migrant. The content of the adjoining text box has been gleaned from the abundance of common dictionary sites available on the internet, and these meanings have been selected to help sort out the appropriate use of each. Precise use of the English language is challenging when we are dealing with international affairs, but we need to get it right - at the very least we must get it right within the Migrant Health Movement. It seems that we have been groping for what to call migratory agricultural workers and their families for a long time; beginning in the Dustbowl era, when displaced sharecroppers left depleted, unproductive land in Oklahoma and Arkansas in large numbers to work in other states (Primarily California and Texas). This group was best described in popular literature by John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath published in 1939, telling the true story of the Joad family. Terms used to refer to this population were derogatory in nature (Okies and Arkies) and did little to recognize the dignity of impoverished families willing to uproot themselves and cross a desolate country, desperate in search of work for sheer survival. The use of the term Bracero was introduced in 1943 with the legalization of Mexico’s contribution to the Allied War effort. The Bracero Program authorized Mexican citizens to work temporarily in the U.S, to replace the U.S farm boys who were fighting in the European War theatre. During that period more than 4.5 million Mexican citizens were legally hired to work in agriculture in the U.S. In CBS’s Harvest of Shame in 1960, Edward R Murrow respectfully uses the term migratory workers in Belle Glade, Florida at a time when the majority of workers there appear to be either of either Anglo or of African descent. The powerful impact of that CBS documentary can be found in the original Public Health Service (PHS) Act 329, that was signed into law by President JFK in 1962. You will see that the terminology used throughout the law is Migratory and Seasonal Agricultural Workers. It is in placing the name on the Act that the term migrant is used, ie the Migrant Health Act. The majority of that original terminology continues today in the PHS 330 legislation which preserves funding for migratory and seasonal agricultural workers. |

The National Center for Farmworker HealthImproving health care access for one of America's most vulnerable populations Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed