|

Next week, members of the NCFH team will gather in Albuquerque, New Mexico for the 25th Annual Midwest Stream Forum. In light of recent global events, the importance of terminology in our work remains a persistent and important subject that merits intentional discussion and reflection. The content below constitutes an extended version of NCFH CEO Bobbi Ryder’s remarks in the Forum’s welcome letter.

These few days represent a unique opportunity for us to come together, share experiences, and explore new ideas in hopes of influencing the Migrant Health Movement’s progress toward increasing access to quality care for agricultural workers in the United States.

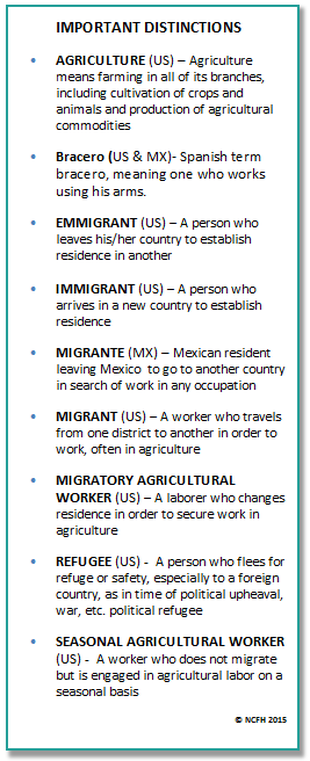

In light of our gathering and some tragic global events of late, many specific details related to our work seem more compelling to me now more than ever. For many decades the use of the word migrante by our colleagues in Mexico was thought by many to mean the same as its cognate, migrant in the English language, thus leading to confusion between immigrants, documented or undocumented, and domestic migratory agricultural workers. Because of such word associations the term migrant has come to connote a stigma and reduces the stature of this vital workforce. Recent publicity about the plight of those fleeing Syria to Europe and the U.S. caught my attention with of the interchangeable use of the terms migrant and refugee. European opposition to the arrival of these refugees evokes images of a largely unwanted and abused population with little sympathy for the terror that they seek refuge from. Calling them migrants both diminishes the reality of the political strife in Syria, adds confusion to popular understanding of the term migrant. The content of the adjoining text box has been gleaned from the abundance of common dictionary sites available on the internet, and these meanings have been selected to help sort out the appropriate use of each. Precise use of the English language is challenging when we are dealing with international affairs, but we need to get it right - at the very least we must get it right within the Migrant Health Movement. It seems that we have been groping for what to call migratory agricultural workers and their families for a long time; beginning in the Dustbowl era, when displaced sharecroppers left depleted, unproductive land in Oklahoma and Arkansas in large numbers to work in other states (Primarily California and Texas). This group was best described in popular literature by John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath published in 1939, telling the true story of the Joad family. Terms used to refer to this population were derogatory in nature (Okies and Arkies) and did little to recognize the dignity of impoverished families willing to uproot themselves and cross a desolate country, desperate in search of work for sheer survival. The use of the term Bracero was introduced in 1943 with the legalization of Mexico’s contribution to the Allied War effort. The Bracero Program authorized Mexican citizens to work temporarily in the U.S, to replace the U.S farm boys who were fighting in the European War theatre. During that period more than 4.5 million Mexican citizens were legally hired to work in agriculture in the U.S. In CBS’s Harvest of Shame in 1960, Edward R Murrow respectfully uses the term migratory workers in Belle Glade, Florida at a time when the majority of workers there appear to be either of either Anglo or of African descent. The powerful impact of that CBS documentary can be found in the original Public Health Service (PHS) Act 329, that was signed into law by President JFK in 1962. You will see that the terminology used throughout the law is Migratory and Seasonal Agricultural Workers. It is in placing the name on the Act that the term migrant is used, ie the Migrant Health Act. The majority of that original terminology continues today in the PHS 330 legislation which preserves funding for migratory and seasonal agricultural workers.

So successful was the Bracero Program that it continued until 1964, 19 years after the end of WWII, making clear our dependence on this Mexican agricultural labor force, as returning soldiers found better paying work in industry. Why should we be surprised that international migration patterns established over 31 year period of time would continue after the end of the Bracero Act?

The 1990s saw a shift from use of the word migrant in the names of health centers, national organizations and committees, to use of the word farmworker. The early adopters of this less inflammatory term were the National Association of Community Health Centers’ (NACHC) Migrant Health Committee, and the National Migrant Resource Program morphing to the Farmworker Health Committee and the National Center for Farmworker Health (NCFH), respectively. More recently, we at NCFH have been using and promoting use of the term Agricultural Workers. This term is free of the stigma and mixed messages associated with the word “migrant”, and it more fully encompasses the understanding that ‘agriculture means farming in all of its branches’ including work in animal as well as horticultural cultivation and production. With the launch of the joint NCFH and NACHC AG WORKER ACCESS campaign, we have also increased emphasis on proper verification of agricultural workers and their family members, reaching out to serve those who do not yet have access, and expanding health center capacity nationwide. At the National Center for Farmworker Health, we strive to build champions for agricultural worker health by taking an active part in the development, encouragement and support of leadership within our community. As we share experiences this week, and collaborate to collectively increase access to care for the population we serve, let’s absorb the lessons inherent in the sessions on management, administration, and migrant health history. Let’s seize these special opportunities to provide essential support for Migrant Health and Increase Access to Quality Care and remember to change the paradigm by consciously using the term agricultural workers in order to confer the maximum dignity. While this paradigm shift will surely call for changes in name and function within the movimiento, I trust that simply changing our spoken and written vocabulary will be an effective step to reduce the stigma and confusion that have come to be associated with the word migrant. Sincerely, Bobbi Ryder NCFH CEO

Join the ongoing conversation regarding increased access to quality health care for agricultural workers. Follow #MWSF2015 and #AGACCESS2020 on Twitter (@NCFHTX), Facebook and Instagram (@farmworkerhealth). More updates to come regarding this year's Midwest Stream Forum.

Hear what Jordan's Queen Rania says regarding the utilization of the terms "migrant" and "refugee" (start at 2:30):

Additional Resources:

Title graphic created with Piktochart.

Comments are closed.

|

The National Center for Farmworker HealthImproving health care access for one of America's most vulnerable populations Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed