|

A woman is a very central, matriarchal, and necessary part of the traditional Hispanic household. Oftentimes one thinks of migrant workers as young men coming to the country to work in the fields. The women who accompany them are too often seen as passive passengers on the dangerous journey many migrant workers face each season.

The month of March honors Women’s History Month. It is important to take time and show recognition for the strong women in the fields who are much more than a passive voice accompanying their male counterparts. “There is no question,” great civil rights and farmworker activist Dolores Huerta says, “that our women are strong. They work right alongside the men in the fields.” And when the day’s labor is done the women go home, cook for their families, help their children with homework or if they’re younger, bathe and feed them. It is very rare that the female farmworker takes time for herself, and she rarely asks for it. There is too much work to be done. Ms. Huerta is right, there is no question whether America’s farmworking women are strong. The question is; how do we give this silent population a voice? According to Cultural Survival there is little known information on the health status of migrating women in the United States. Undocumented female workers face unique barriers, among them, poor occupational health and safety, poor diet, and most are unfamiliar with the affordable health services they are eligible for. The barriers mentioned above do not exclusively affect women. However, one fear that women have reported more frequently than migrant men is the fear of sexual abuse. Many migrant women do not report cases of sexual assault because they fear repercussions. Nearly 50% of the migrant agricultural workforce are undocumented immigrants; too often women remain silent because of their fear of termination or deportation. In the rare occasion that a woman reports abuse, it is usually lengthy process that is not sustainable or affordable for a low-income migrating family. It goes without saying that sexual abuse can cause physical and emotional harm to our women in the fields, especially when abusers are not charged for their crimes. So what can we do to help our mothers, sisters, and daughters in the fields? Community Health Workers and Promotoras de Salud can go out in the fields and educate both men and women on what constitutes as sexual abuse. There are some laws that protect our female farmworkers as well. Abuse in the fields is unacceptable. Abuse in the fields without knowing how to access health services is unacceptable. The National Center for Farmworker Health is calling on Migrant and Community Health Centers to increase their number of farmworkers served to 2 million by the year 2020. No one should fear their mortality or safety because of lack of access to primary and preventative health care services. Find out other ways you can get involved to help women in the fields raise their voices. Photo Credit: iStock One in every ten Hispanic/Latino persons will develop Diabetes Type 2 after the age of 20, according to the National Diabetes Education Program. Of those 10%, nearly 12% are of Mexican ethnicity. The ethnically Mexican population, both documented and undocumented, accounts for 68% of the Agricultural Worker population in the United States.

Naturally, with Diabetes risk factors being higher within Latino populations, it is important for special vulnerable populations – like the United States’ Migrant Agricultural Workers – to have provided to them the important tools and resources for both understanding the risk of Diabetes and how to manage it if diagnosed. Diabetes Type 2 (or Diabetes Mellitus) happens when our bodies cannot process glucose (or sugar) like it used to. Sugar levels rise and our bodies try to make up for it by producing more insulin. However, after time the body cannot regulate the process and thus Diabetes Type 2 is diagnosed. Symptoms of Diabetes Type 2 often include feeling fatigued, thirsty, numbness in the feet and hands, blurred vision, and higher susceptibility to cuts and bruises that won’t heal. Agricultural Workers face a greater risk due to their specific barriers to health care. Lack of health insurance and transportation are big factors. But Dr. Keshelava also reported that workers might fear the retaliation of their superiors if they are feeling sick. Retaliation can be hours cut or being fired. The good news is there are ways to manage Diabetes Type 2 within the migrant Agricultural Worker population. A collaborative Farmworker Health Network member, MHP Salud, has programs that train Community Health Workers to go out in the fields and offer culturally appropriate education on Diabetes Type 2. NCFH, in coordination with Consumer Reports Best Buy Drugs, has created low-literacy and culturally appropriate factsheets for Migrant Health Centers to provide patients who have been diagnosed with Diabetes Type 2. Written By: Mindy Morgan Photo: iStock  Perhaps unlike many, my connection to the American agricultural production system exists through living relatives. In a sleepy small town in Tennessee, my grandparents still reside in a one-story, ranch-style house amidst miles of farmland, although they no longer work their land themselves or manage the harvesting of crops - and haven’t since retiring. As a child, I remember running through tall cornstalks chasing my sisters and avoiding bees. I remember small bean plants and rides on my grandpa’s John Deer tractor. I remember long discussions of the poor planting decisions of neighbors and dismay at the piece-by-piece selling of land in the area for economic survival. Even with these fond memories and close encounters with our nation’s changing food production system, I still consider my understanding of the lives of migrant and seasonal ag workers relatively infantile. Fortunately, I found my premier attendance at NCFH’s Annual Midwest Stream Forum served as a giant gateway to increasing that understanding. From explanatory sessions on how U.S. social programming addresses the unique needs of ag workers to fervent discussions of how to champion increased access to health care for this population, I found myself in a diverse community of advocates, researchers, public health leaders and front-line health service delivery workers. We were all curious to hear each other’s stories and perspectives, anxious to build on our tools for meeting the needs of those who keep America fed. This year’s Keynote Speaker, Judge Juan Antonio Chavira, provided attendees with valuable insight into the importance of accommodating, respecting and recognizing the influence of curanderismo, Mexican American folk healing, when treating some agricultural worker patients. He said our prerogative as champions of ag worker health should not be to convince someone that their way of healing is incorrect but that both fields of thought might work together to meet patients’ needs. Instead of being right, “the idea is to make people well,” he said. On behalf of NCFH, thank you so much to everyone that attended and supported this year’s event in Albuquerque. On behalf of myself, a fellow learner and growing champion, may the lessons and conversations from the forum continue to inspire us to better serve agricultural workers in innovative, respectful and culturally appropriate ways. By Lindsey Bachman Photos: Lindsey Bachman A few notable resources highlighted at this year's forum:

Join the ongoing conversation regarding increased access to quality health care for agricultural workers. Follow #MWSF2015 and #AGACCESS2020 on Twitter (@NCFHTX), Facebook and Instagram (@farmworkerhealth). This year's Midwest Stream Forum was about growing champions of migrant health. Tell us about how you champion migrant health by leaving a comment below.

Behavioral and mental illness disorders remain part of a large conversation among the American public, and recent events make the need for depression and other mental health disorder screenings a must for health centers that serve the vulnerable communities in our country. Community Health Centers (CHCs) realize the very real concern of behavioral health issues among these populations. Nearly 70% of CHCs are screening for depression and other related mental health disorders around the nation, while 40% provide substance abuse counseling and treatment. According to the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC), “Persons living with mental illness have a higher mortality rate and often die prematurely due to preventable diseases such as: diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory diseases, and infectious diseases.” The good news? There has been a dramatic growth in assessing the quality measures of behavioral health within the last decade. Although there is a growth in assessment, there is still work to be done. U.S. migrant and agricultural workers suffer with a higher susceptibility to the risks of behavioral health and its diagnosis. Migrant agricultural workers who are separated from their families may be more susceptible to mental health disorders, such as depression, alcoholism, and substance abuse. Nervios is a “culturally defined definition of stress.” A study conducted by National Agricultural Worker Survey (NAWS) reported that 20% of male agricultural workers experienced some form of Nervios and those who were separated from their families had reported a higher rate at 28%. When behavioral and mental health goes untreated, the results can be devastating on a personal and communal level. Many untreated disorders result in patient suicides, incarceration, homelessness and severe episodes of violence. To find a Community Health Center offering depression screening please visit: http://findahealthcenter.hrsa.gov/ By Mindy Morgan

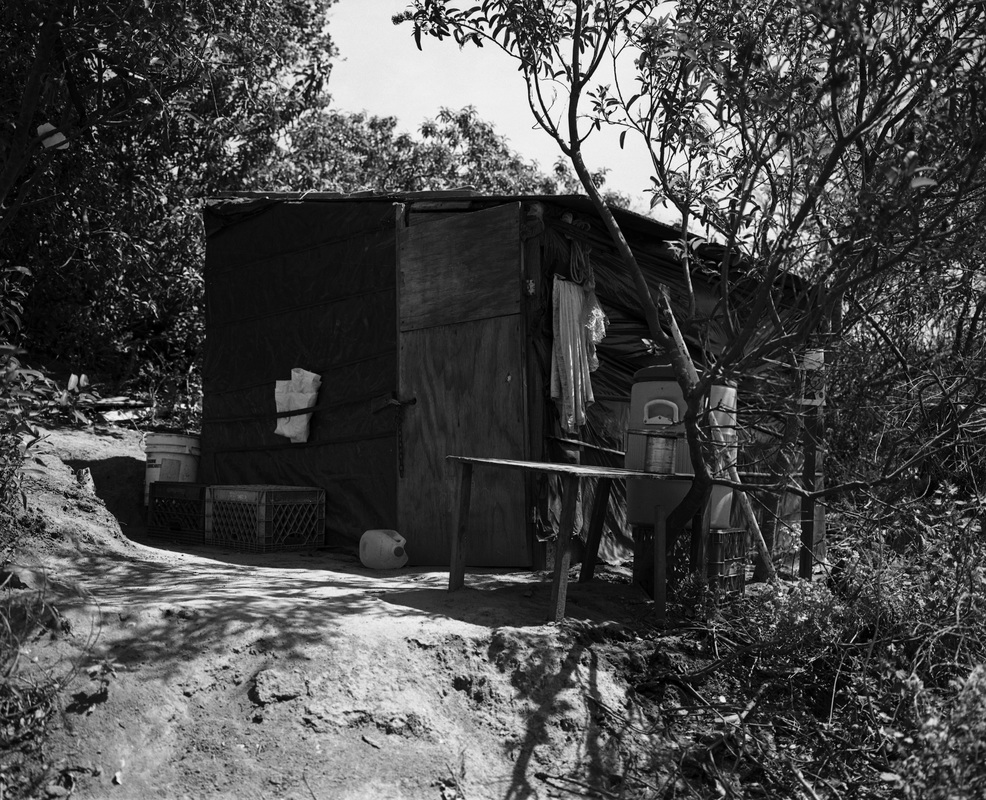

Photo: Alan Pogue Although there has been substantial progress in cancer treatment, screening, diagnosis, and prevention over the past several decades, addressing cancer health disparities—such as higher cancer death rates, less frequent use of proven screening tests, and higher rates of advanced cancer diagnoses—in certain populations is an area in which progress has not kept pace. These disparities are frequently seen in people from low-socioeconomic groups, certain racial/ethnic populations, and those who live in geographically isolated areas. – National Cancer Institute  The U.S. Latina population has lower-rates of breast cancer than non-Hispanic women. However, they have a 20% greater chance of dying than other women after receiving a positive diagnosis. Many attribute this discrepancy to the social determinants of health that influence patient survival – including a lack of access to quality education and healthcare, which is exacerbated by patients’ socioeconomic statuses. The unique seasonal and migratory lifestyles of female agricultural workers further compound and complicate these issues – as do the effects of existing misinformation regarding screenings and cultural beliefs amongst this population. The necessity of consistent appointments and follow-ups for effective care proves problematic for those on the move and those working under severe occupational time constraints. Women over the age of 50 are urged to get annual mammograms in addition to performing frequent self-examinations. However, a positive exam only constitutes an initial step in the breast cancer diagnosis process. Patients must return and provide a tissue sample before the disease is confirmed. Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) served more than 2 million women over the age of 50 and 440,000 women utilized services at Migrant Health Centers in 2014. FQHCs also performed more than 470,000 mammograms and found almost 110,000 breast abnormalities last year. The National Center for Farmworker Health recognizes the need for a special focus on breast cancer outreach to the U.S. female agricultural worker. Through its Cultivando la Salud program, NCFH offers health centers and other Hispanic-serving organizations the opportunity to receive train-the-trainer instruction intended to provide program planners with the knowledge, step-by-step process, and the tools to successfully plan and develop a comprehensive breast and cervical cancer education program for the agricultural population as well as other Hispanic communities. The training includes basic program planning information from designing the program goals and objectives to developing a budget to recruitment and training of lay health workers. The program also includes an evaluative component and specialized focus on the teaching tools lay health workers will be using in the community. At the end of the training, training participants will be provided with a complete training curriculum, a program manual to guide the implementation of the program, and the CLS teaching tools for lay health workers to use in the community. By Lindsey Bachman

Photo: Steve Debenport, iStock Are you interested or do you know a good candidate for the National Advisory Council on Migrant Health (NCAMH)? HRSA's Bureau of Primary Health Care is soliciting nominations for membership for 4-year terms starting November 26, 2015. The NACMH advises, consults with, and makes recommendations to the Secretary of Health & Human Services (HHS) regarding the direction HHS should take in providing health care for migratory and seasonal agricultural workers and their families. View this fact sheet for more information and apply today!

|

The National Center for Farmworker HealthImproving health care access for one of America's most vulnerable populations Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed